Practice Pattern Survey: What is Popular Practice in 2024 and How Does It Compare to Current Standards?

Brian Taylor, Au.D. and Kevin Liebe, Au.D.

“What is right is not always popular and what is popular is not always right.” —Albert Einstein

Spend some time at Facebook’s Audiology Happy Hour and you will see no shortage of hot takes on how or why various clinical tests or procedures should be conducted. Online forums might be a great place to share thoughts, ideas, and opinions on a variety of topics related to the practice of audiology, but how often do these views reflect best-practices? Ideally, there should not be a noticeable difference between popular practice, best defined as the tests and procedures conducted by the majority of audiologists, and best-practice, which is supported by scientific principles. As the Einstein quote attests, what is popular and what is right (supported by science) are often not one in the same.

Through a combination of innovative technological breakthroughs and emerging research that comes from well-designed studies, clinicians can refine their approach to the identification and treatment of hearing loss. However, many new ideas and approaches, even when supported by research don’t always displace the inertia of popular practice: What we learned in school and in our early training may no longer be the “gold standard” of care, but many stay mired in their tried-and-true way of doing things, despite new evidence that doesn’t support it.

As Doctors of Audiology, it is incumbent upon all of us to stay abreast of emerging evidence that could modify or even change the way we deliver care. But, considering the busyness of our daily lives, it is often difficult to break old habits and add a new wrinkle to our assessment protocol or workflow that might have better efficacy. Fortunately, we can rely on published standards and guidelines to direct us.

There is no shortage of clinical audiology guidelines that can be applied to the hearing aid selection and fitting process, although many of them are probably outdated. Since 1990, numerous hearing aid selection and fitting guidelines have been published including the Vanderbilt Report (1991), the Independent Hearing Aid Fitting Forum (1997), AAA’s Adult Fitting Guidelines (2005) and others. More recently, the Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO) created a series of practice standards that can be implemented clinically to best achieve high quality patient outcomes. Regardless of the specific set of guidelines, there are several important reasons, according to Valente (2006), that necessitate following current guidelines:

- Promote uniformity of care

- Decrease variability of outcomes

- Promote better fitting practices

- Elevate the clinical care to our patients as well as elevate our profession

- Provide greater patient satisfaction

- Reduce the hearing aid return rate

Both standards and guidelines* are typically created by a panel of experts with decades of collective experience who create the standards after considerable vetting and debate. Once the panel agrees upon the standards or guidelines, they are published, or like in the case of the APSO standards, archived on a website. Given that the APSO adult hearing aid selection and fitting standard has had a chance to percolate for a few years (reviewed by Mueller et al, 2021), three years post-publication of the APSO standard for fitting adults with hearing aids seems like a good time to gauge if that standard has changed practice patterns.

Rationale and Methods

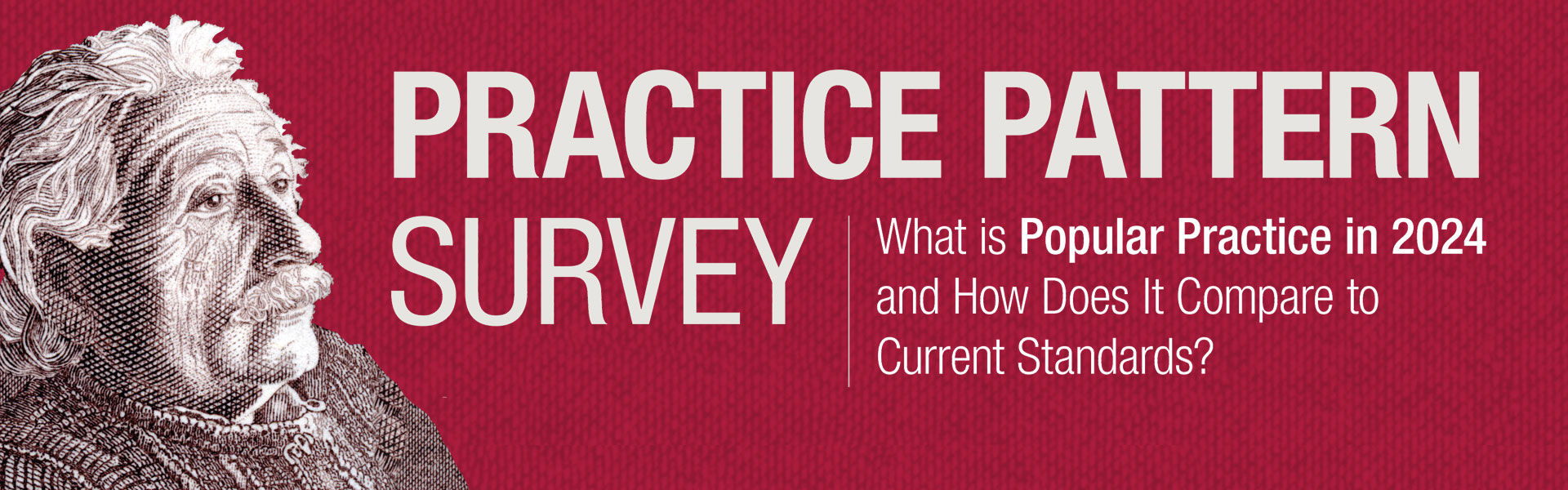

With an eye toward what might be considered best-practice, the aim of this survey was to assess what is popular practice in 2024. Further, the purpose of this survey was to obtain additional insights on how the APSO standards for fitting hearing aids on adults might be used by workaday clinicians who are juggling many responsibilities throughout their week. Toward that end, a 30-question survey was created in August 2023. The electronic survey was emailed on two separate occasions in October and November 2023 to a segment of the Hearing Healthcare Technology Matters (HHTM) database, comprised of 5,859 US-based audiologists. Of those receiving the emailed survey, 1824 opened the email and the entire survey was completed by 186 audiologists. Figure 1 shows the various clinical settings reported by these 186 respondents with the plurality of them working in a private practice setting.

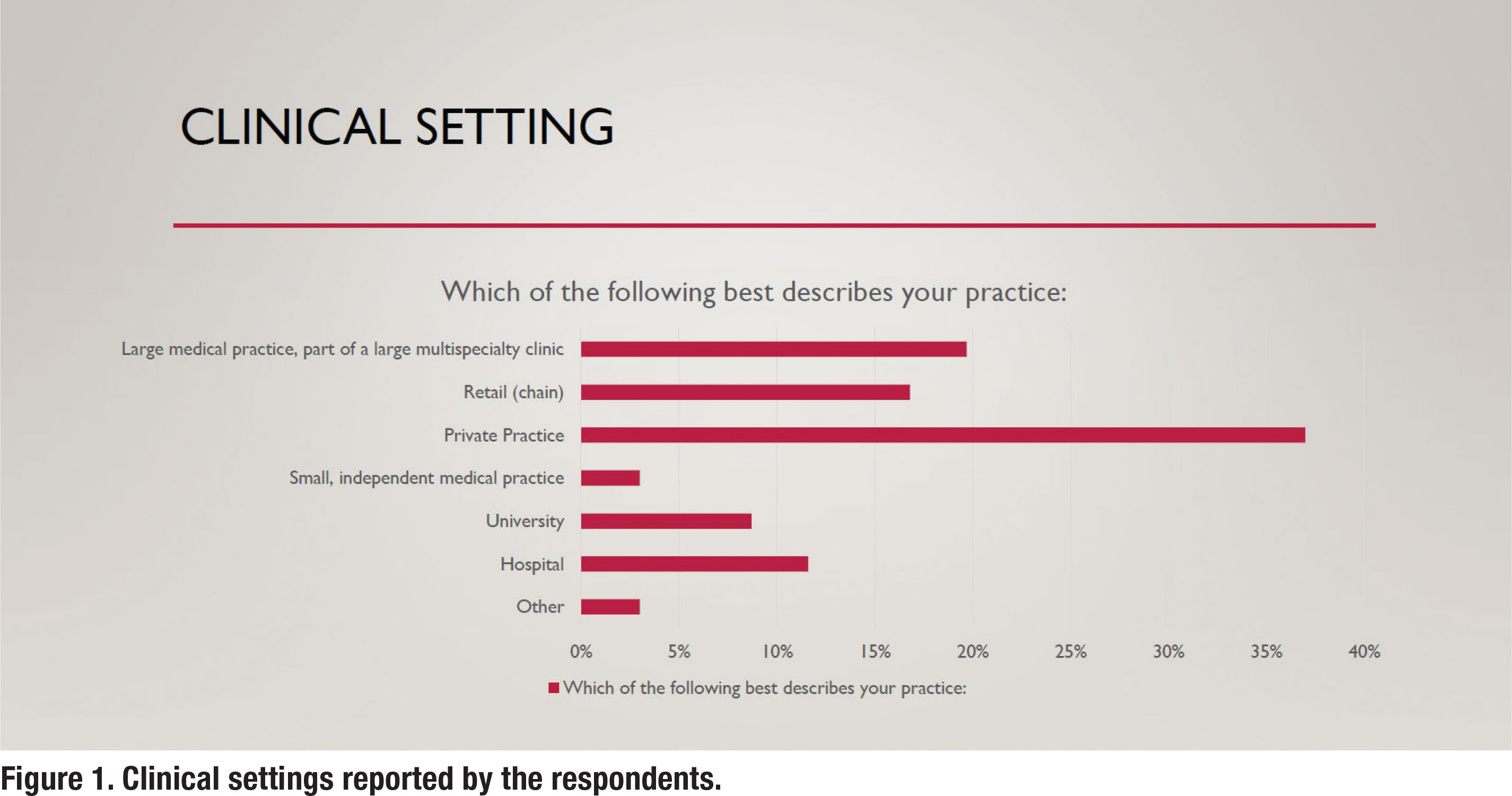

In addition to their clinical settings, the respondents were asked about their years of clinical experience. Figure 2 summarizes the self-reported years of experience for the respondents. The mean years of clinical experience was 14.2 years.

Section 1: Clinical Procedures

The first half of the survey was devoted to specific clinical procedures conducted in the clinic on adult hearing aid prospects and candidates. The questions were sequenced in a manner similar to how adult patients would be assessed in the clinic, beginning with a communication needs assessment and ending with verification and validation procedures. The recently published APSO guidelines for fitting hearing aids on adults and geriatric patients (S2.1) served as a framework for the design of the questions. That is, survey questions were created that corresponded with several elements of the S2.1 standard. Additionally, other bestpractice guidelines were used as a basis of comparison.

The Top-2 Box responses were used to determine what is “popular practice.” Specifically, the Top-2 Box responses “always” and “routinely” were summed to determine what is “popular practice.”

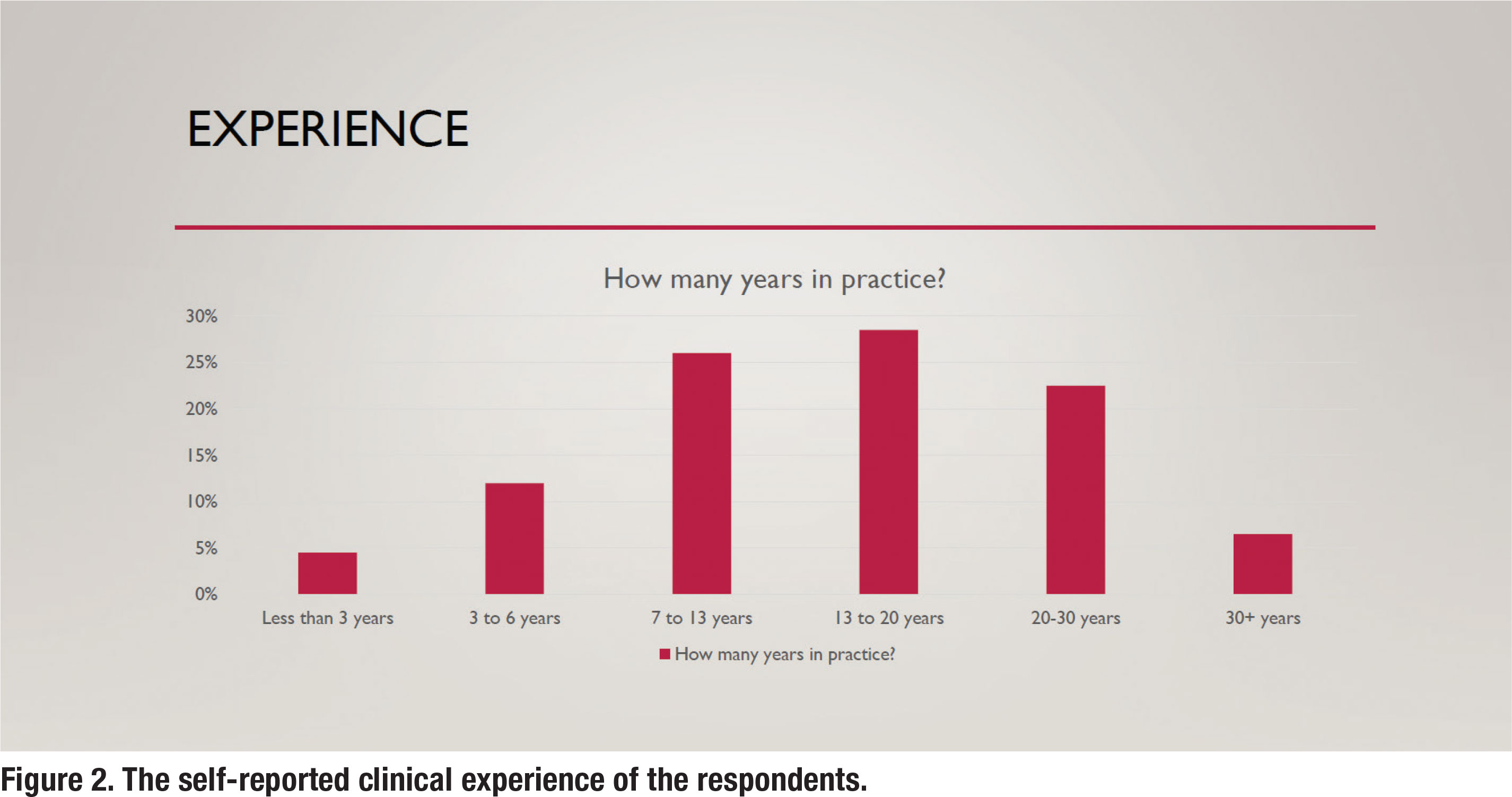

Pre-fitting Communication Needs Assessment

As APSO S2.1 asserts, “a needs assessment is conducted in determining candidacy and in making individualized amplification recommendations. A needs assessment includes audiologic, physical, communication, listening, self-assessment, and other pertinent factors affecting patient outcomes.” Figure 3 shows the results for the question, how often do you complete a standardized needs assessment for a new patient. According to the survey, 69% of respondents routinely conduct a needs assessment using a standardized approach.

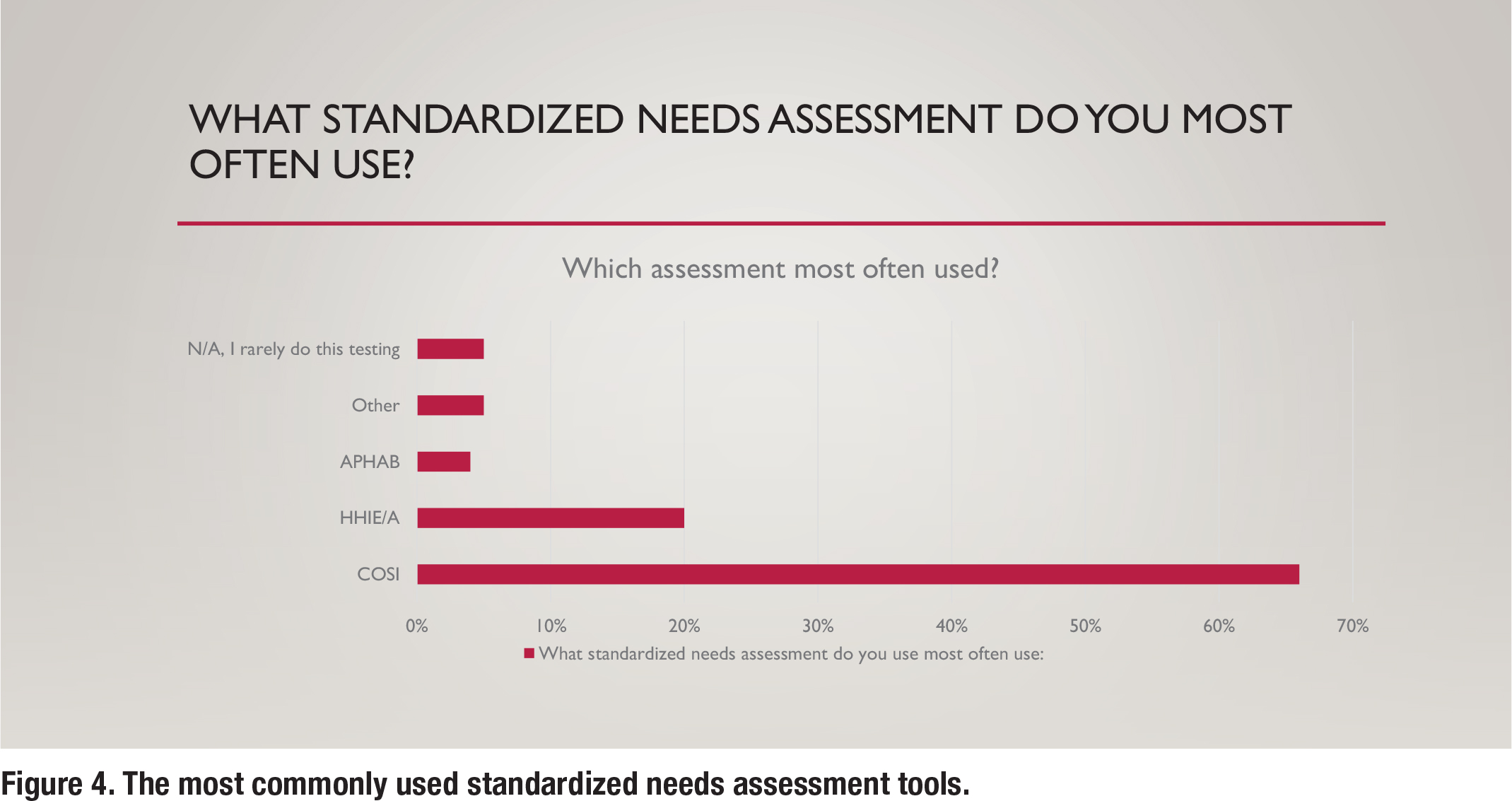

Although the APSO standard is confined to “what” tests are recommended, additional information in this survey was gathered to understand “how” certain tests are conducted in the clinic. Figure 4 shows the various types of standardized communication needs assessments that are conducted in the clinic. By far, the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) is the most popular needs assessment used by respondents.

Pre-fitting Word Recognition in Quiet Testing

Although the APSO S2.1 standard makes no reference to conducting word recognition in quiet (WRQ) testing, APSO S3.1 Comprehensive Diagnostic Hearing Evaluation for Adult Patients says, a measure of speech recognition ability is obtained using recorded stimuli at a presentation level that is expected to approximate the patient’s maximum performance. Additionally, there are specific guidelines outlining exactly how WRQ testing should be conducted. These guidelines, summarized by Mueller and Hornsby (2020) include the following:

- A presentation level that ensures audibility. The “2k + xSL” approach, outlined by Guthrie & Mackersie (2009), is the current standard approach to presentation level.

- Use of the recorded NU-6 “ordered by difficulty” 50-word list and conclude testing if the patient passes the screening guidelines.

The use of a recorded NU-6 ordered by difficulty word list has been part of standard WRQ testing for decades while the accepted standard practice for presentation level was published more recently in 2009. Further, the entire updated procedure that reflects current standards for WRQ testing has been published in its entirety twice: Hornsby and Mueller (2013) and Mueller and Hornsby (2020).

The survey asked a series of questions to ascertain if clinicians routinely conduct WRQ testing using these standards. According to the survey, 98% of respondents routinely conduct WRQ testing. However, the methods in which they conduct WRQ testing varies.

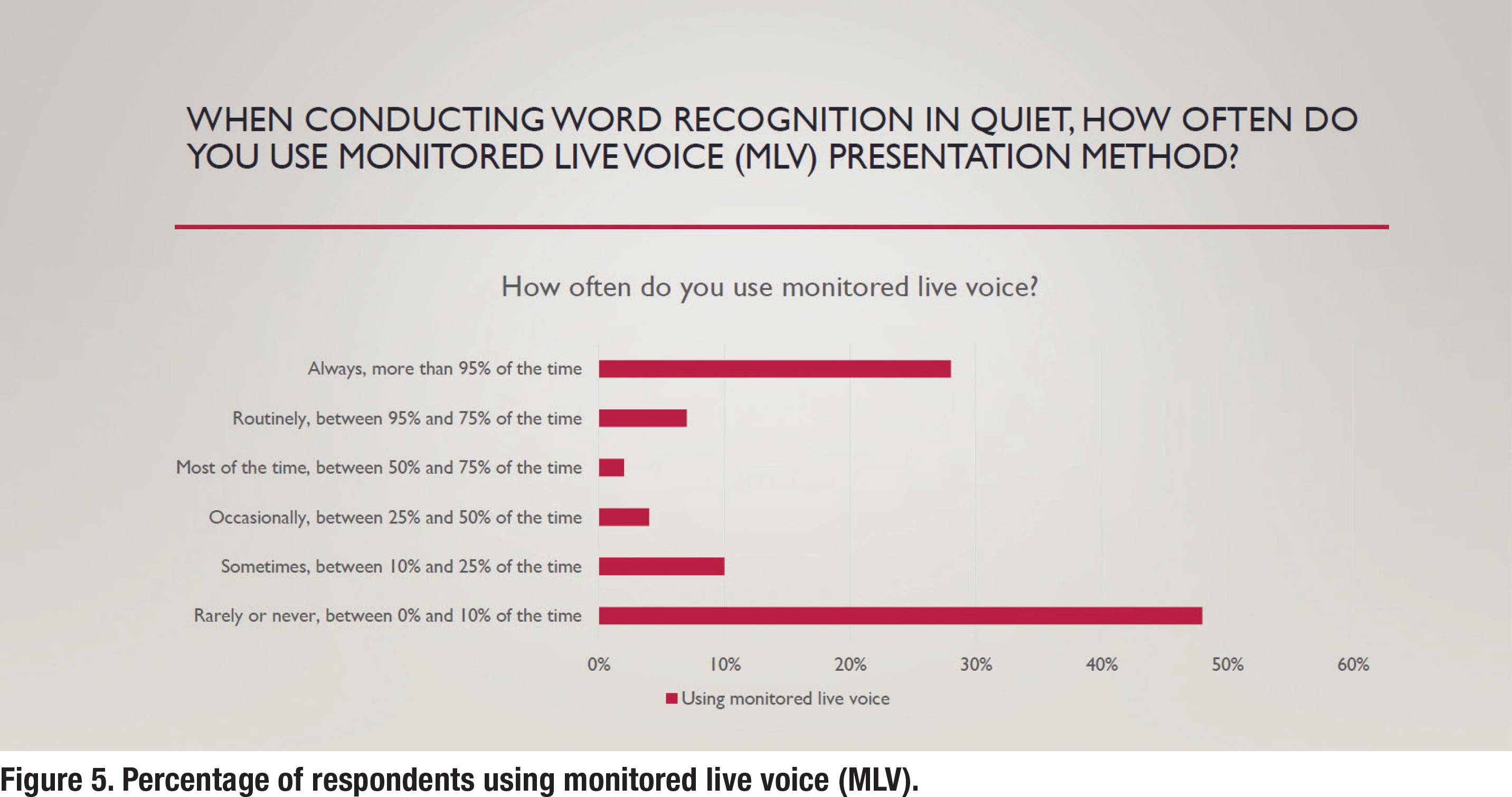

As Figure 5 shows, just under half (48%) of respondents indicated that they never use monitored live voice (MLV). In contrast, popular practice (52% of respondents either routinely or part of the time) is to rely on MLV. Use of MLV, according to the standards outlined by Mueller N Hornsby (2020), render WRQ testing invalid.

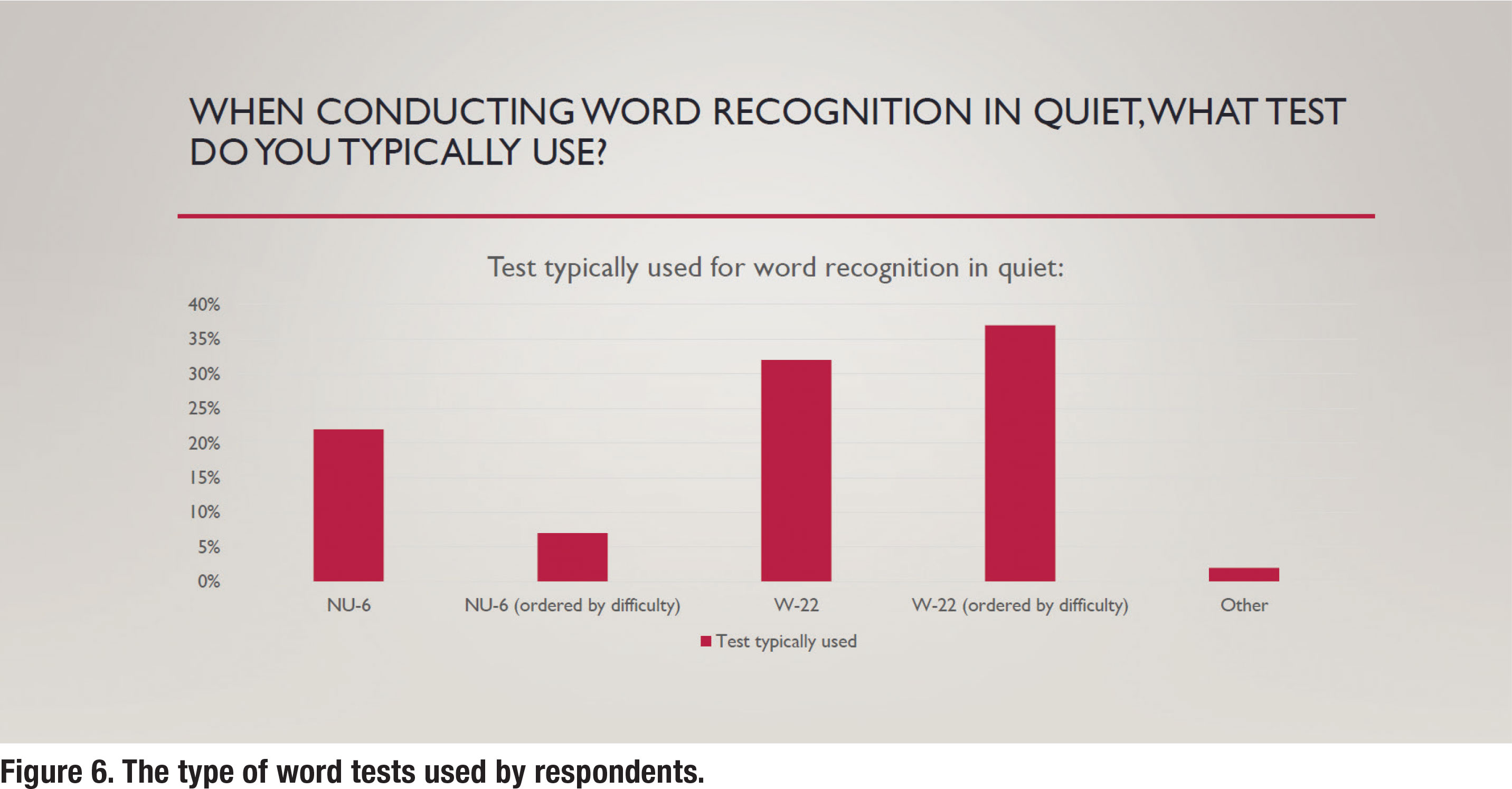

As previously mentioned, the word list used to complete WRQ testing is an essential component of valid completion of this assessment. Both the W-22 and NU-6 have enjoyed widespread clinical use. However, because the NU-6 recording is “ordered by difficulty” it can be used in a validated way to shorten WRQ testing if the patient passes the screening guidelines. It is quite surprising, as depicted in Figure 6, that the W-22 is much more popular than the NU-6 and by a massive 69% to 30%.

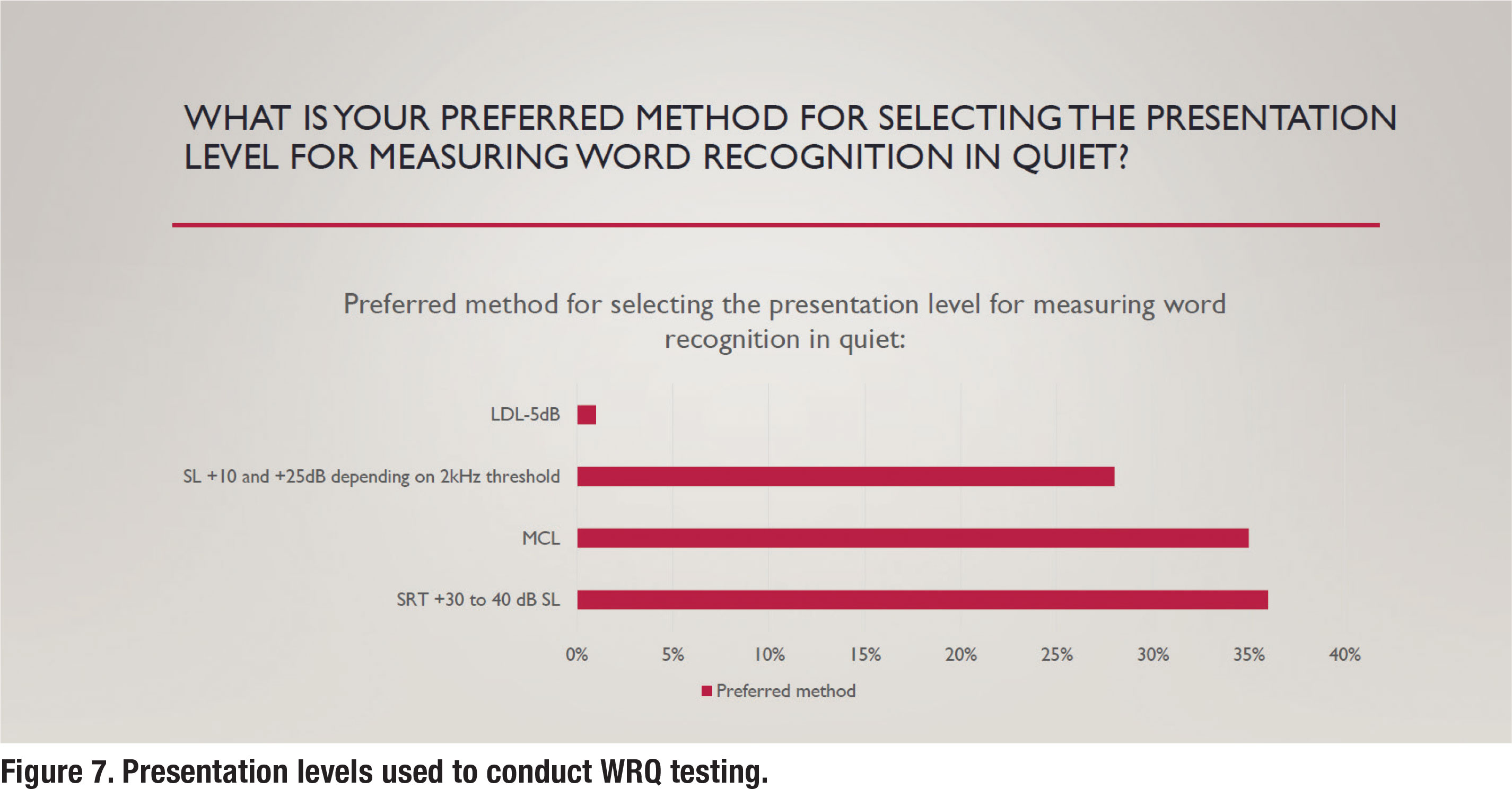

As also previously mentioned, the presentation level for administering WRQ testing was established by Guthrie and Mackersie in 2009. In a nutshell, their approach uses the sensation level above the 2000 Hz threshold of the patient to establish the presentation level. Further, in their “2k + xSL” approach, when it is not feasible to conduct the test at this presentation level, the clinician should conduct WRQ testing at a “level just below the patient’s uncomfortable loudness level (LDL).” According to Hornby and Mueller (2013), this approach replaces the antiquated “SRT + 30 or 40 dB SL” or “MCL” approaches. Unfortunately, according to the survey, those antiquated approaches are still the most popular, as shown in Figure 7. Results indicate that about one-third of respondents use the current standard approach outlined by Guthrie and Mackersie (2009) when conducting WRQ testing.

Pre-fitting Speech in Noise and LDL Testing

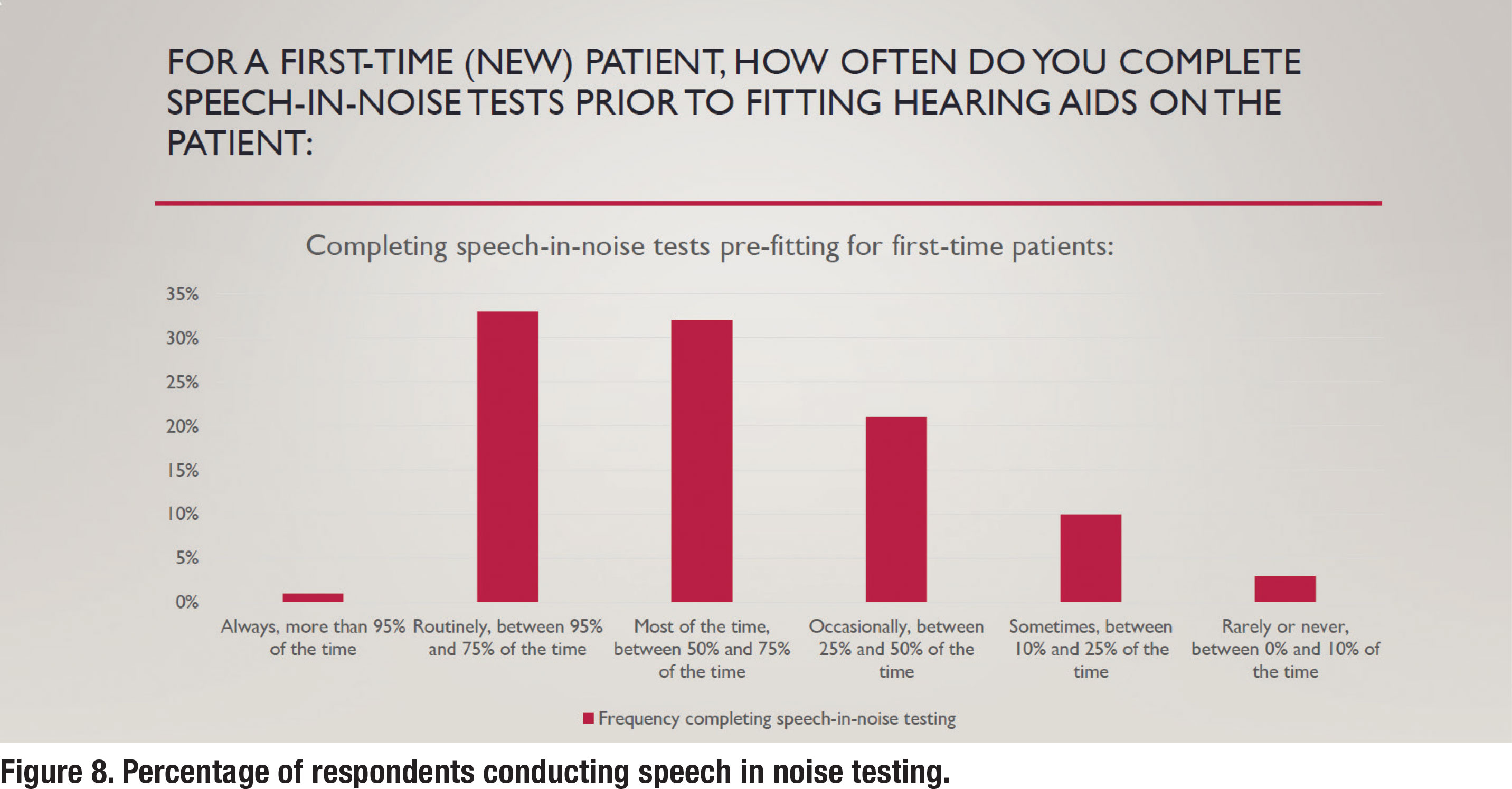

As outlined in APSO standard S2.1, pre-fitting testing includes assessment of speech recognition in noise, unless clinically inappropriate, and frequency-specific loudness discomfort levels. As shown in Figure 8, approximately one-third of respondents reported that they routinely conducted speech in noise testing prior to selecting and fitting hearing aids. The most popular speech in test was the Quick SIN with 78% of respondents who routinely conduct speech in noise testing reporting they use that test. The other 12% who routinely conducted speech in noise testing used a smattering of other speech in noise tests including the AZBio, HINT and Words in Noise (WIN) test.

In accordance with the APSO standards that call for speech-in-noise testing to be part of the pre-fitting assessment, a recent award-winning peer reviewed article (Fitzgerald, et al, 2023) called for the Quick SIN to replace WRQ testing as part of the routine diagnostic hearing assessment. Based on their analysis of 5808 individuals undergoing Quick SIN testing, the predictive power of their model suggested that the Quick SIN can replace WRQ in most instances. They provided guidelines as to when performance in quiet is likely to be excellent and does not need to be measured. As the authors propose, switching practice patterns from WRQ testing to the Quick SIN as the default speech test would enable routine audiometric assessments to be more sensitive to patient concerns, and would benefit both clinicians and patients by completing speech testing quicker.

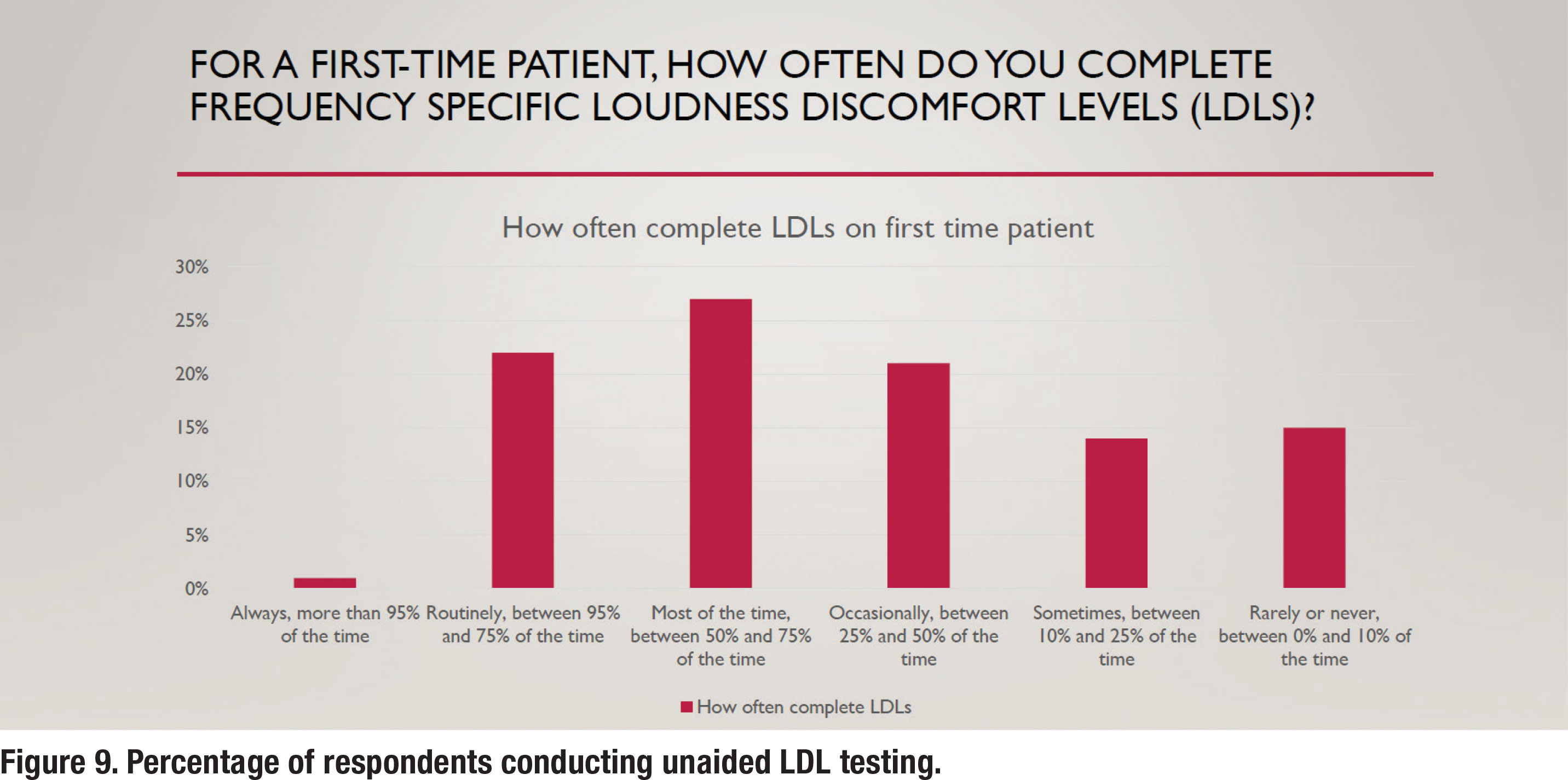

Unaided loudness discomfort level (LDL) testing is also a part of the S2.1 APSO standard. Even though it is part of the standard, it is not a popular practice as less than 25% of respondents (Figure 9) conduct it routinely. Not completing pre-fitting LDL testing implies that the audiologist is relying on either the manufacturer to determine the maximum power output (MPO) of the hearing aid or to use a predicted value that is based on the patient’s threshold. According to data on MPO settings of all six major manufacturer’s devices (Mueller, et al 2021), both these approaches usually lead to MPO settings that are well-below the patient’s measured LDL. In some cases, according to their analysis, low MPOs will make the wearer’s signal to noise ratio worse (when speech is above the noise) and consequently have a negative effect on speech understanding. These findings clearly support the need to conduct frequency-specific LDLs and use these values to program the hearing aids correctly, a practice that less than 25% of respondents conduct routinely.

Electroacoustic and Verification Measures

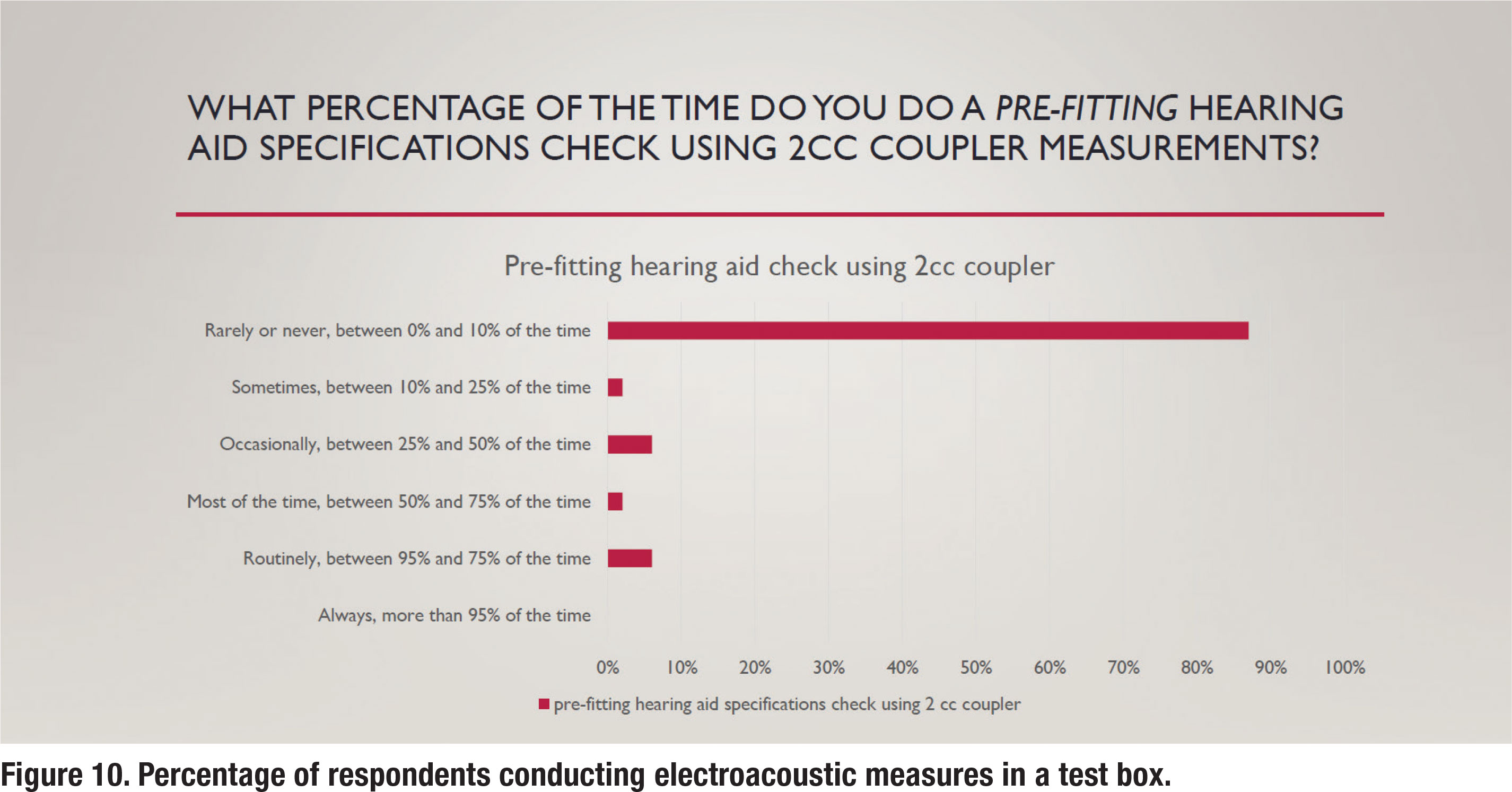

The APSO S2.1 standard calls for an assessment of initial product quality using standard electroacoustic measures to verify either manufacturer or published specifications. Figure 10 illustrates the percentage of respondents that routinely conduct this electroacoustic measurement standard. It shows that about 5% of respondents routinely conduct this measure. This suggests that clinicians trust the manufacturer’s quality control process so much that most do not cross-check published specifications with their own set of test box measures.

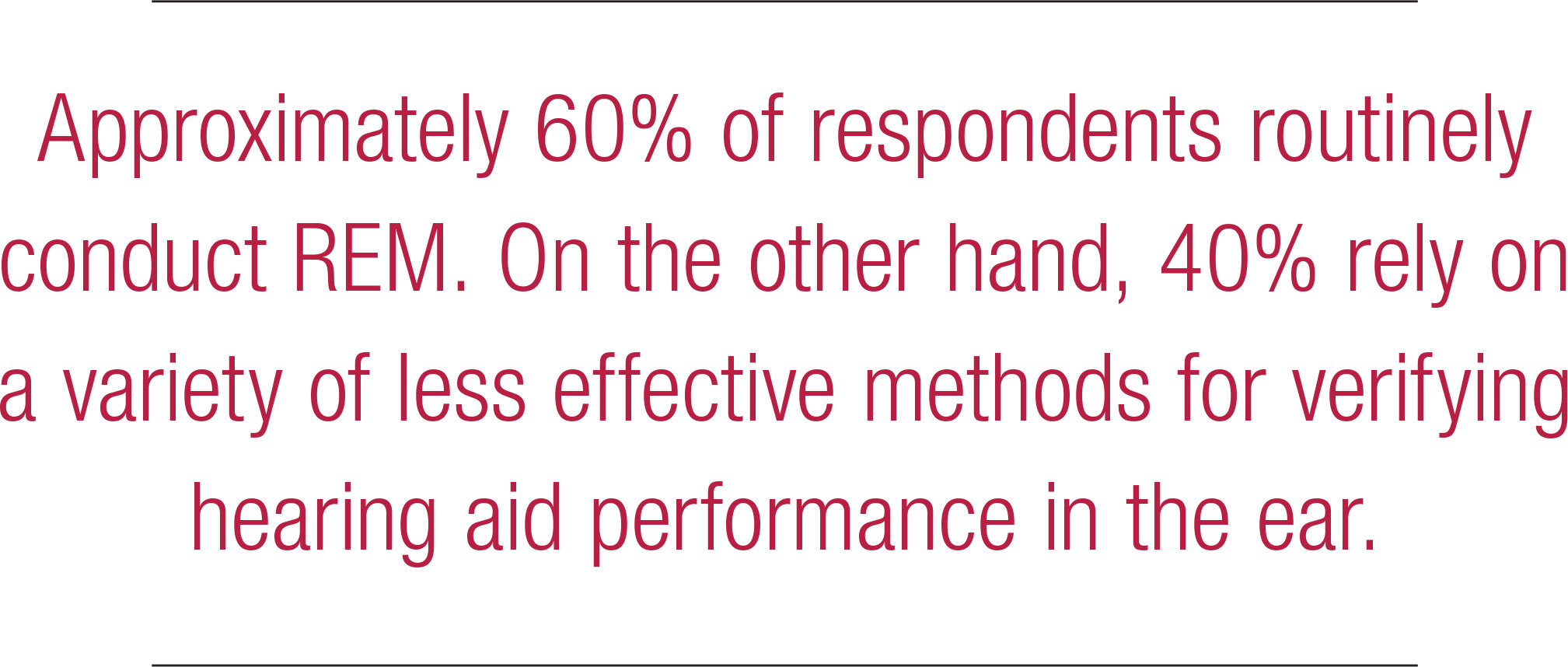

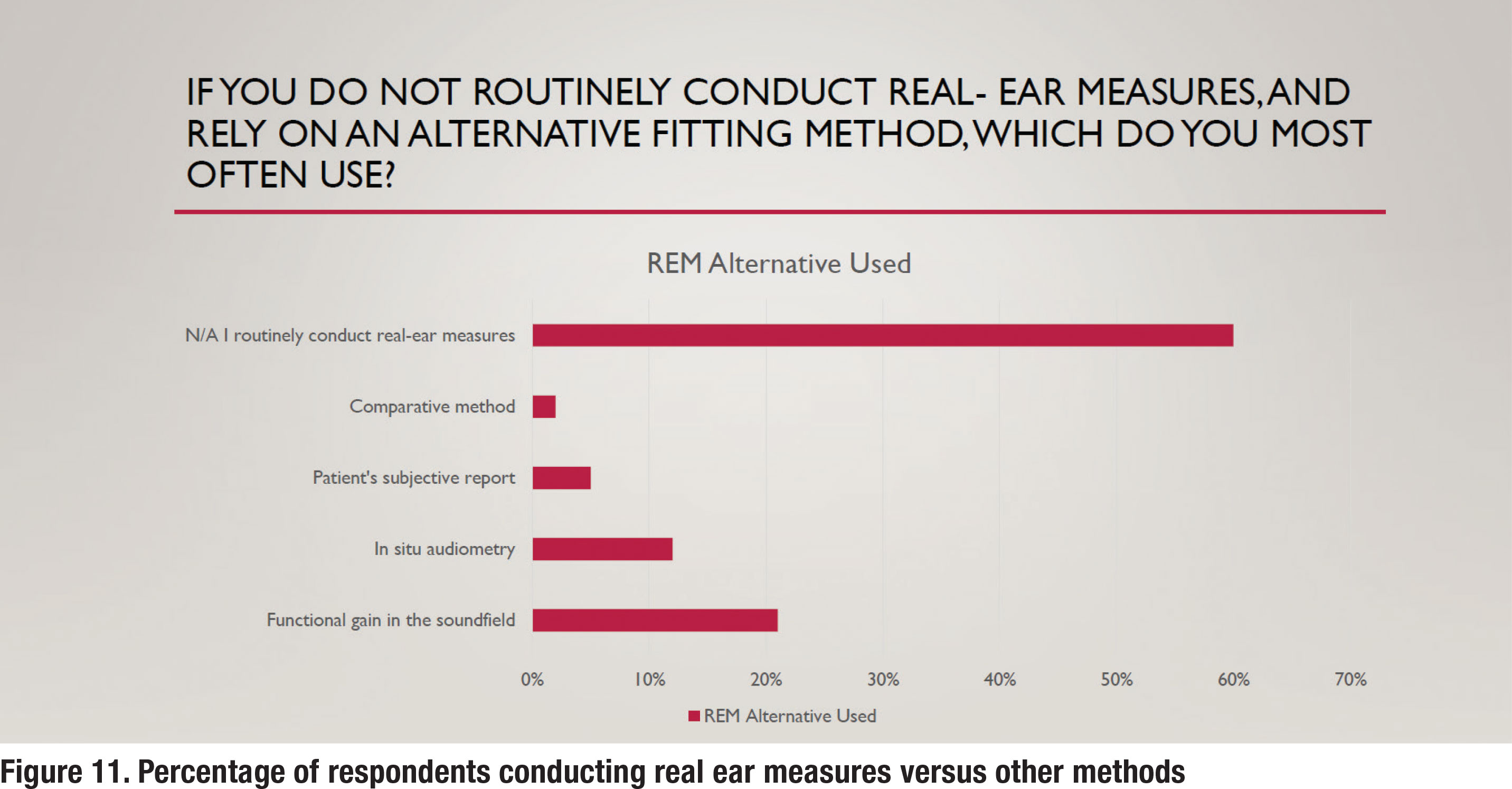

Another essential component of fitting hearing aids is verifying that a prescriptive target has been matched. For decades, real ear measures (REM) have been the established method of verification. The APSO S2.1 standard calls for hearing aids to be fitted so that various input levels of speech result in verified ear canal output that meets the frequency-specific targets provided by a validated prescriptive method. The survey asked several questions to gauge whether any parts of this standard are popular practice. Figure 11 indicates that approximately 60% of respondents routinely conduct REM. On the other hand, 40% rely on a variety of less effective methods for verifying hearing aid performance in the ear.

Another essential component of fitting hearing aids is verifying that a prescriptive target has been matched. For decades, real ear measures (REM) have been the established method of verification. The APSO S2.1 standard calls for hearing aids to be fitted so that various input levels of speech result in verified ear canal output that meets the frequency-specific targets provided by a validated prescriptive method. The survey asked several questions to gauge whether any parts of this standard are popular practice. Figure 11 indicates that approximately 60% of respondents routinely conduct REM. On the other hand, 40% rely on a variety of less effective methods for verifying hearing aid performance in the ear.

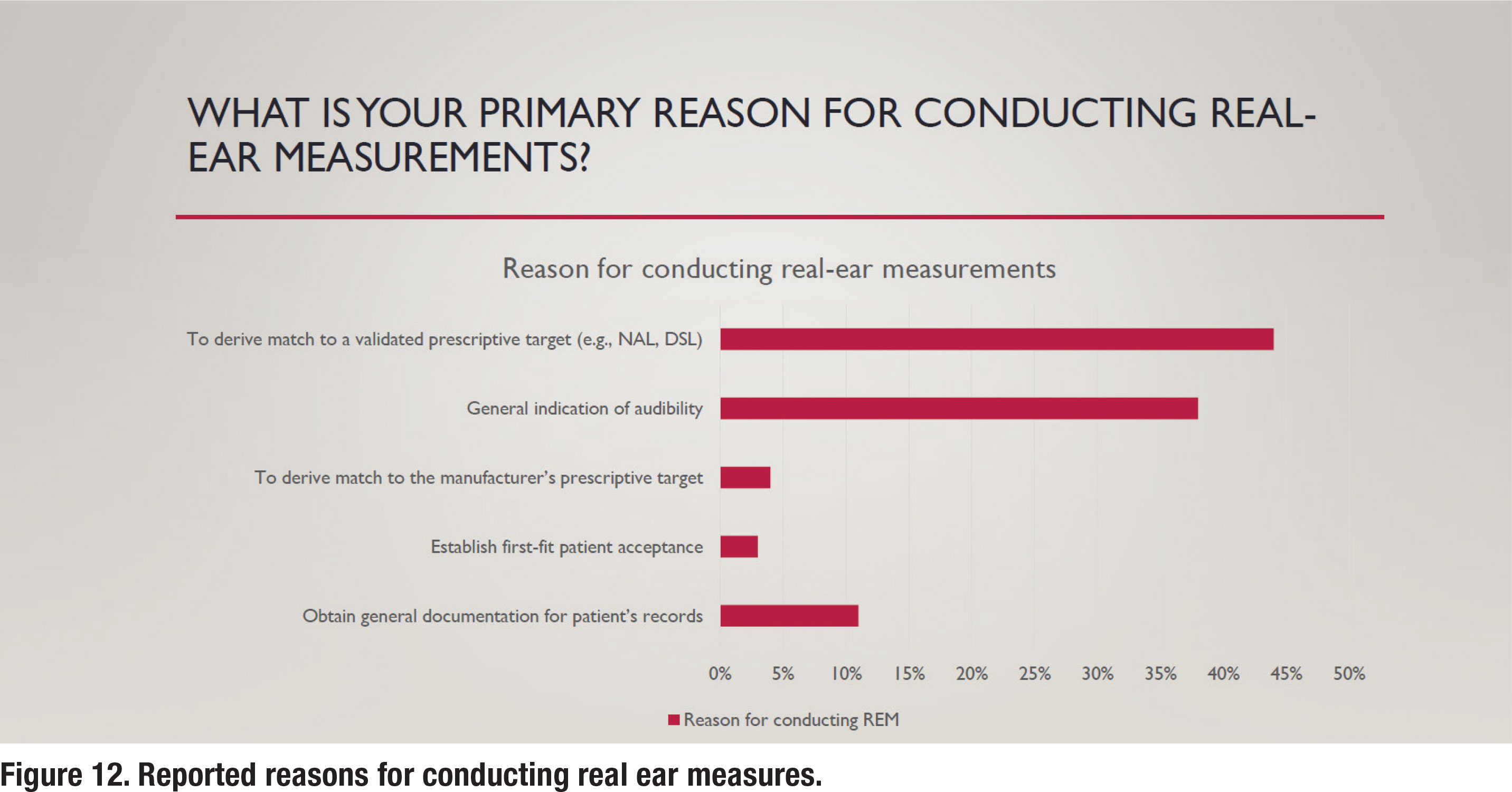

Figure 12 illustrates some of the reasons for conducting REM. As per the APSO standard, a validated prescriptive target, typically either the NAL-NL2 or DSL v5.0, and not a manufacturer’s version of those targets or their proprietary target, would be matched. As noted in Figure 12, 44% of respondents following the ASPO standard, match a validated prescriptive target. Respondents were also queried about the input signal they use when conducting REM. It is well established that a calibrated “speech-like” input signal should be used. According to the responses, about 90% of those routinely conducting REM use a calibrated “speechlike” signal with less than 5% reporting they use an uncalibrated live voice to conduct REM.

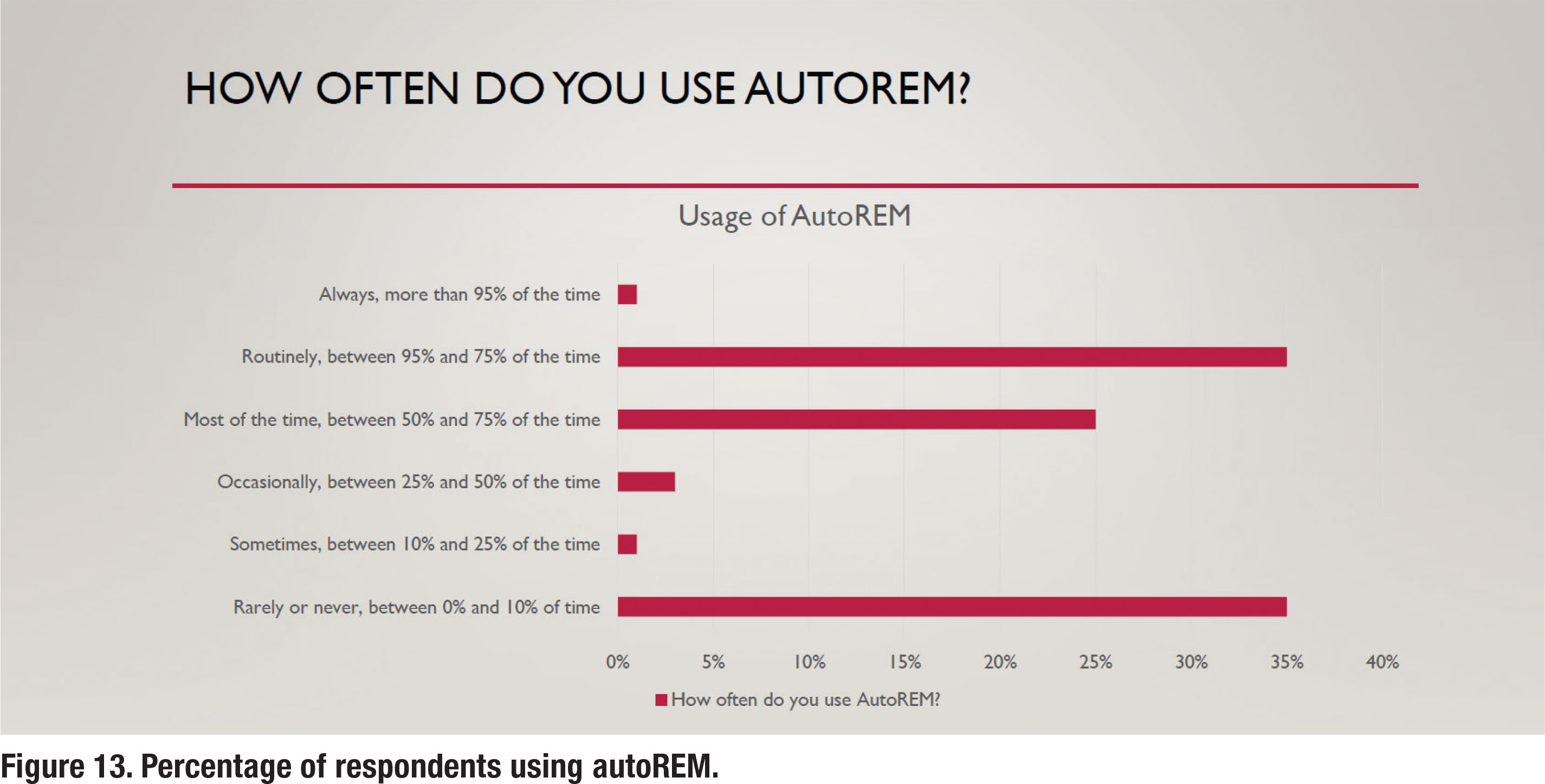

Although not part of the APSO standard, autoREM measures have become widely available from most REM manufacturers. Recall that autoREM allows the REM system and hearing aid fitting software to “talk” to each other, making the verification process more time-efficient. According to the results in Figure 13, about one-third of respondents routinely use autoREM, while another third rarely or never use it.

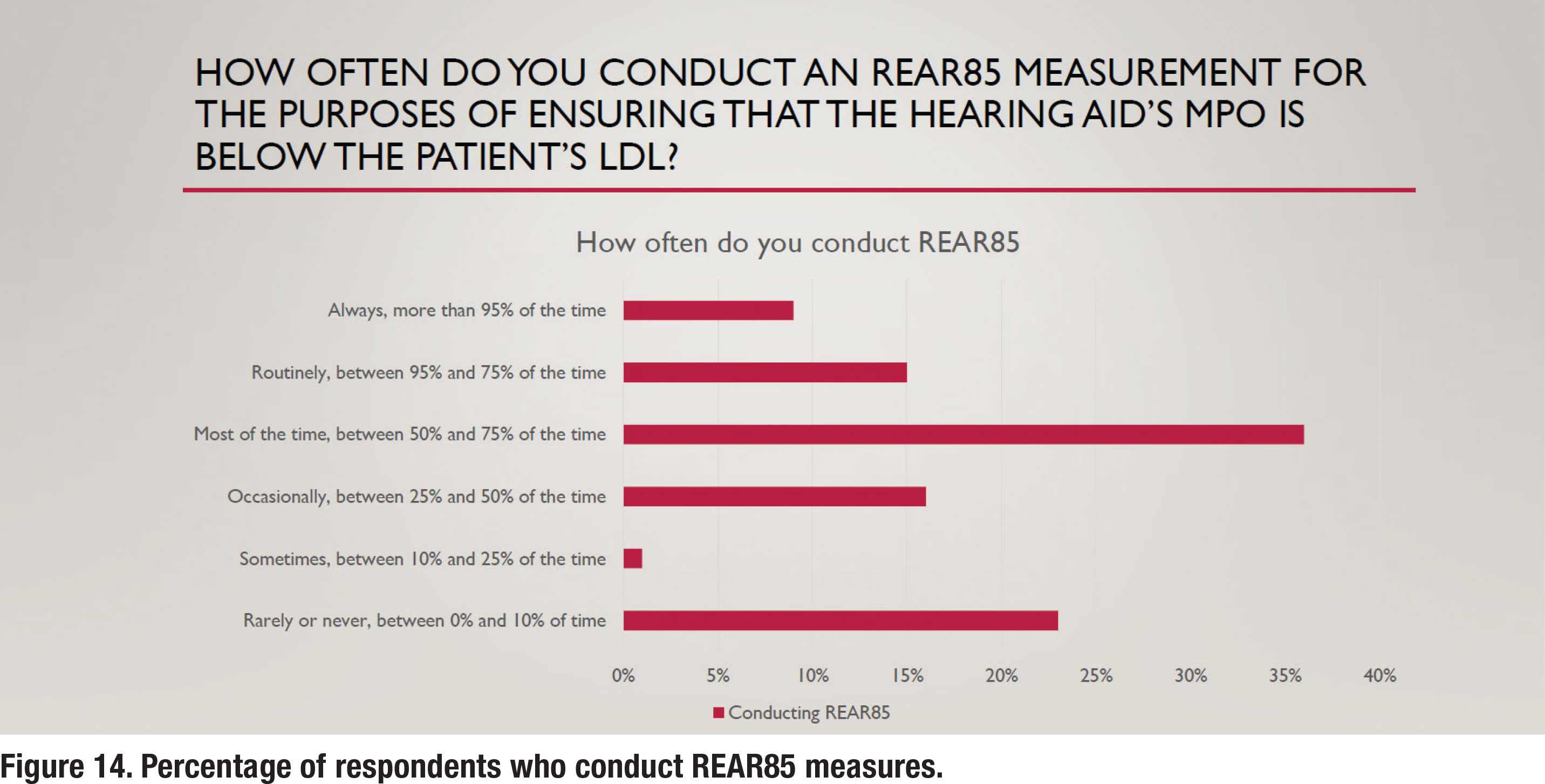

A final APSO standard related to hearing aid verification states that the frequency-specific maximum power output is adjusted to optimize the patient’s residual dynamic range and ensure that the output does not exceed the patient’s loudness discomfort levels. This is a two-step process involving measuring the patient’s unaided LDL and converting that LDL value (in dB HL) to dB SPL, and then using REM to verify that the maximum power output (MPO) of the hearing aid is just below the LDL. The REM term for this is the Real Ear Aided Response for an 85 dB SPL input (REAR85). Recall from Figure 9 that approximately 25% of respondents conduct unaided LDL measures, which is an essential part of the REAR85 measure. Figure 14 shows that just under 25% of respondents routinely conduct REAR85 measures, while an almost equal number rarely or never conduct the REAR85. Thus, measuring the REAR85, an essential part of ensuring the MPO is just under the wearer’s LDL is not a popular practice.

A final APSO standard related to hearing aid verification states that the frequency-specific maximum power output is adjusted to optimize the patient’s residual dynamic range and ensure that the output does not exceed the patient’s loudness discomfort levels. This is a two-step process involving measuring the patient’s unaided LDL and converting that LDL value (in dB HL) to dB SPL, and then using REM to verify that the maximum power output (MPO) of the hearing aid is just below the LDL. The REM term for this is the Real Ear Aided Response for an 85 dB SPL input (REAR85). Recall from Figure 9 that approximately 25% of respondents conduct unaided LDL measures, which is an essential part of the REAR85 measure. Figure 14 shows that just under 25% of respondents routinely conduct REAR85 measures, while an almost equal number rarely or never conduct the REAR85. Thus, measuring the REAR85, an essential part of ensuring the MPO is just under the wearer’s LDL is not a popular practice.

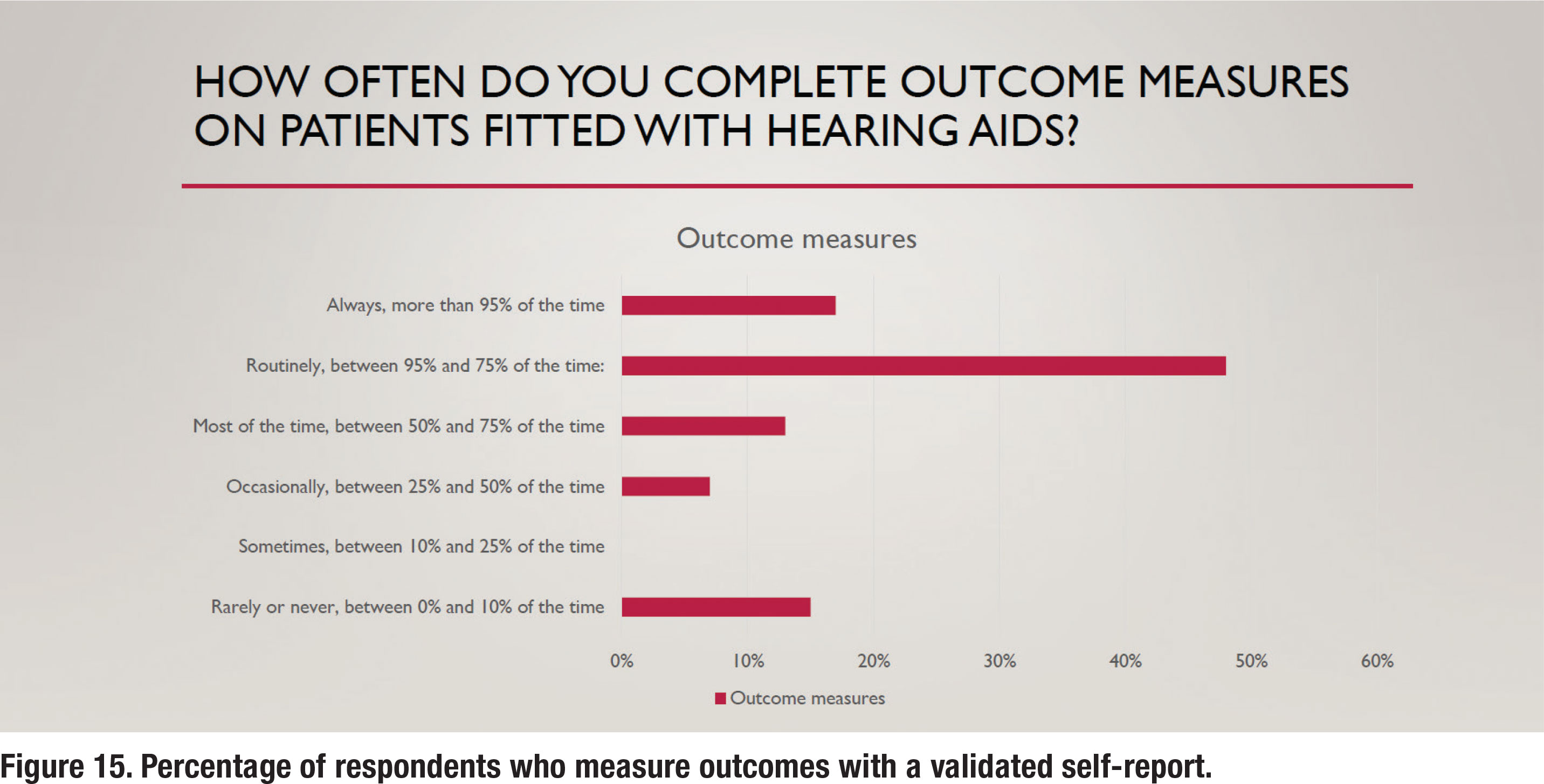

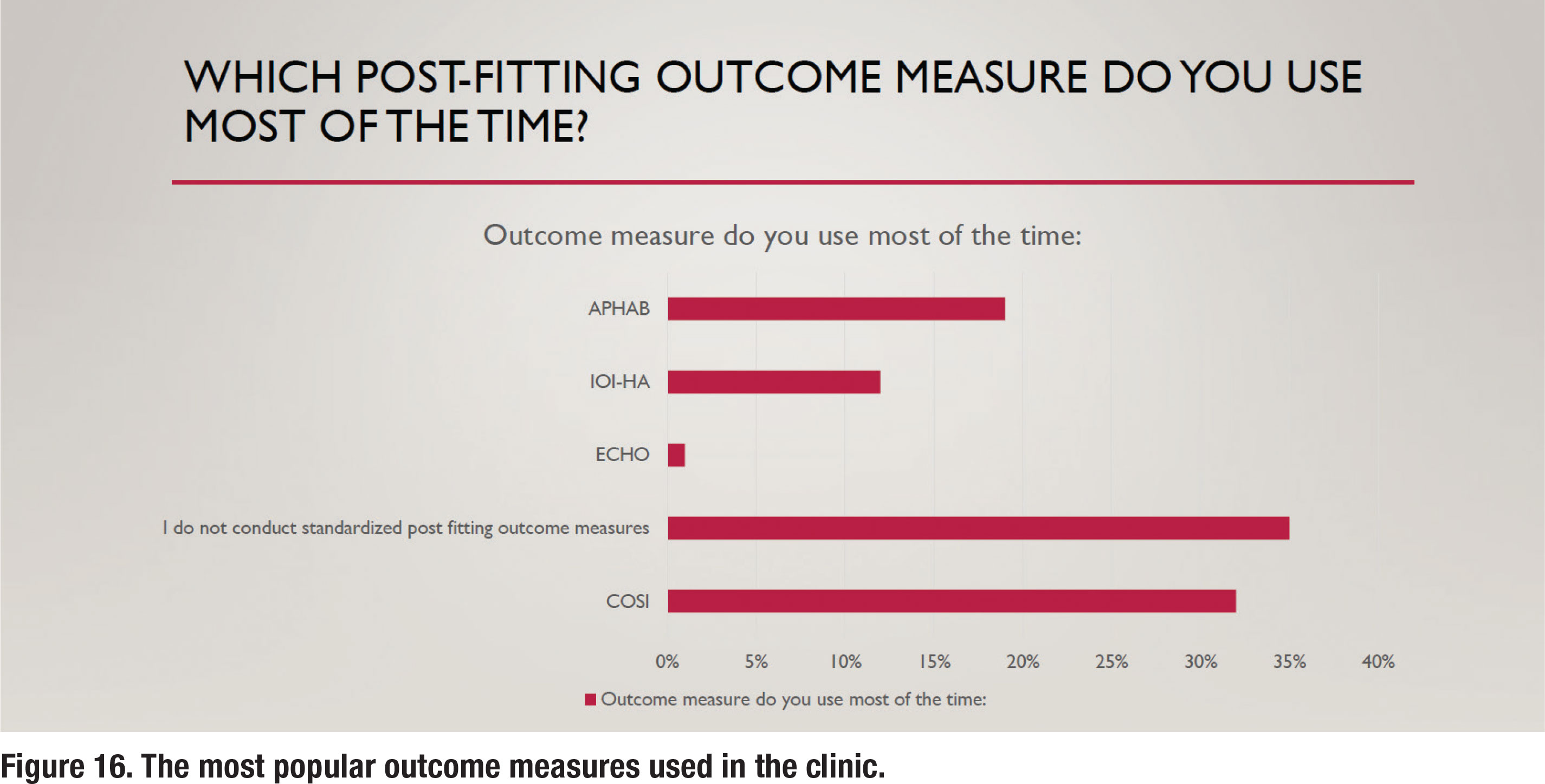

The APSO S2.1 standard calls for the measurement of hearing aid outcomes using a validated self-assessment measure. Results of the survey show that about 65% of respondents routinely measure outcomes with a validated self-assessment, as depicted in Figure 15. Figure 16 shows the self-assessments that are most commonly used in the clinic, with the COSI being the most popular. Figure 16 also indicates that 35% of respondents report that they rarely or never measure outcomes.

Are Custom Earmolds Becoming a Lost Art?

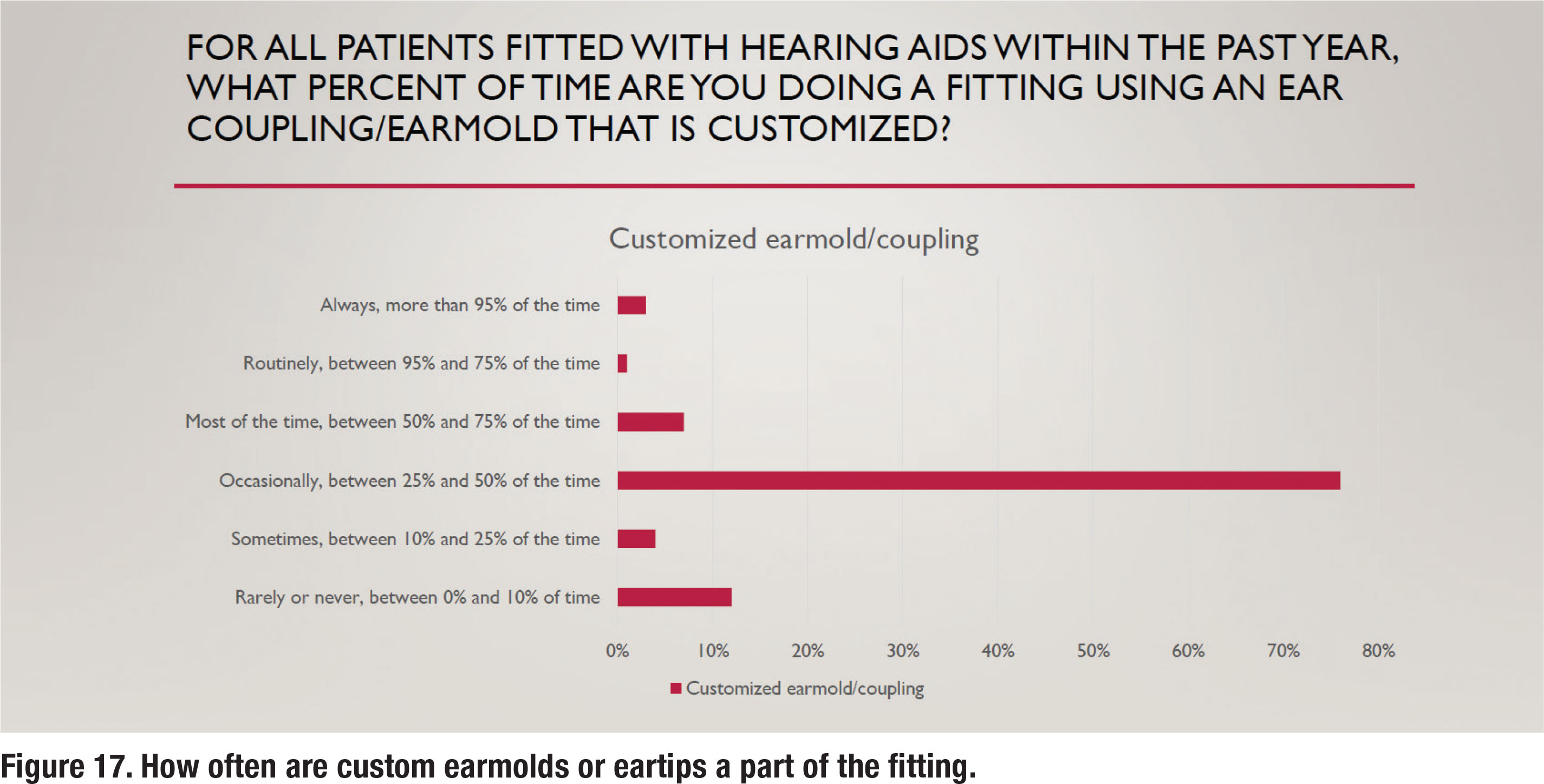

Over the past twenty years, receiver in the canal (RIC) hearing aids have become extremely popular. Along with the RIC style, an instant fit eartip is often recommended. There are several advantages associated with these instant fit eartips, including comfort, concealment, and convenience. There are, however, some disadvantages associated with the use of instant fit eartips, the chief one being the unpredictable nature of slit leak vents that often negate the effectiveness of noise reduction algorithms for low and mid frequency inputs (Balling et al, 2019). Figure 17 illustrates that only 11% of respondents fit custom earmolds/eartips “most of the time” or routinely, suggesting that customization of the ear coupling system is far from a popular practice.

Section 2: Practice Management and Workflow

Part 2 examines various components of managing an audiology practice. With the onset of COVID-19 four years ago, audiologists were forced to rely on remote care services such as tele-audiology. With the pandemic behind us, it seems like a good time to also see if any of these new technologies have found their way into popular clinical use.

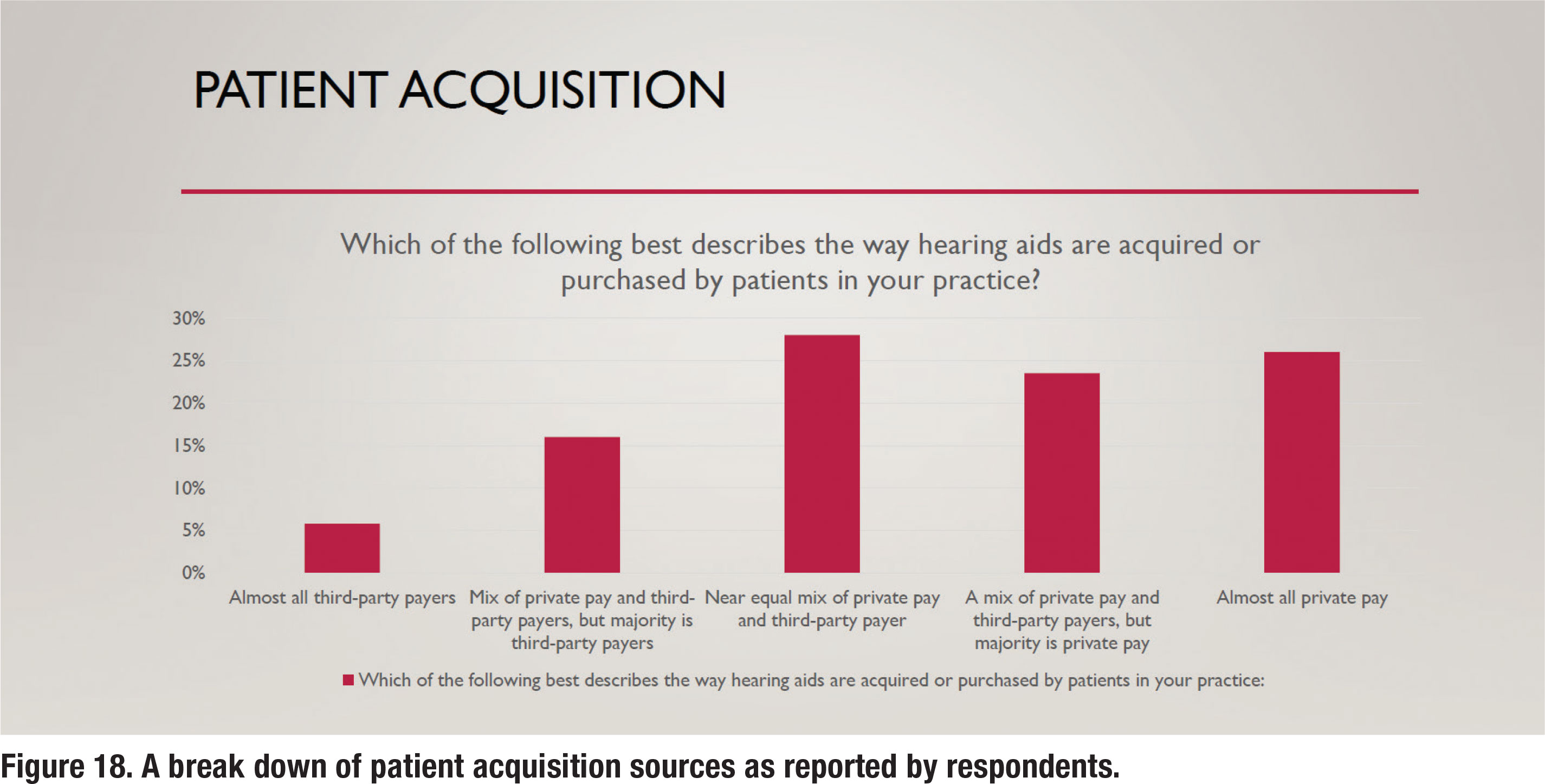

Patient Acquisition

Over the past decade, third-party administrators have become an increasingly larger part of the patient-clinician equation. Although the prevalence of third-party administrators varies a lot by region, most audiologists conduct at least a part of their business with third-party administrative involvement. Figure 18 shows a break down of how much business audiologist conduct with third-party administrators. There is an almost even split between audiologists who report that all or most of their business is private pay versus those who report that all or most of their business comes from third-party payers. Note that nearly onequarter of respondents report that all of their business continues to originate from private pay sources.

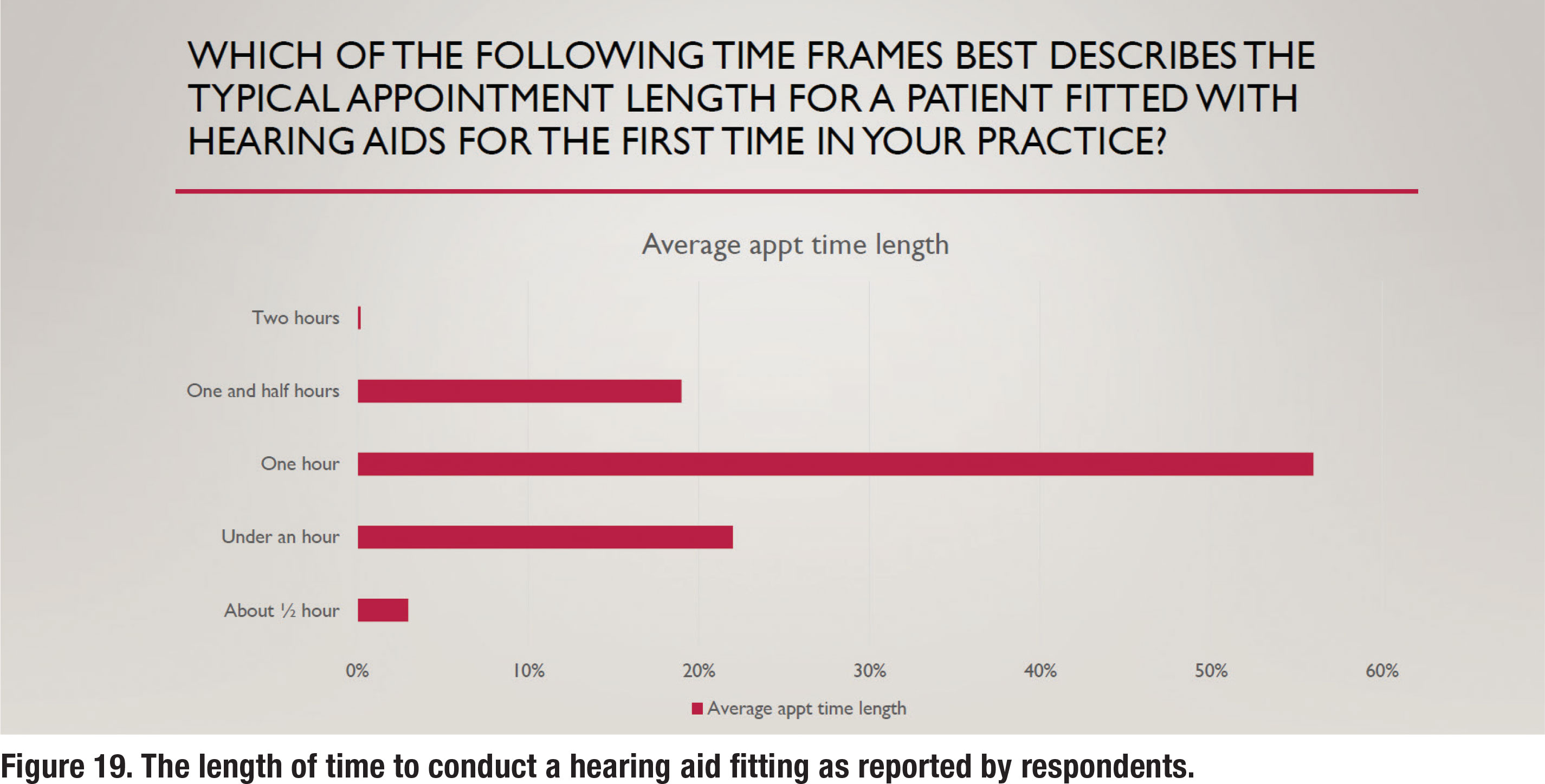

Time Spent with Patients

Since a primary focus of this survey was common procedures used to fit hearing aids on adults, two questions pertaining to how time was spent with patients were asked. Figure 19 shows the average length of time devoted to fitting hearing aids on a new patient, with 56% of respondents stating the average appointment length was one hour and an equal number (~20%) stating the average length was either under one hour or 90 minutes. Follow-up care is another important component of managing a thriving audiology practice.

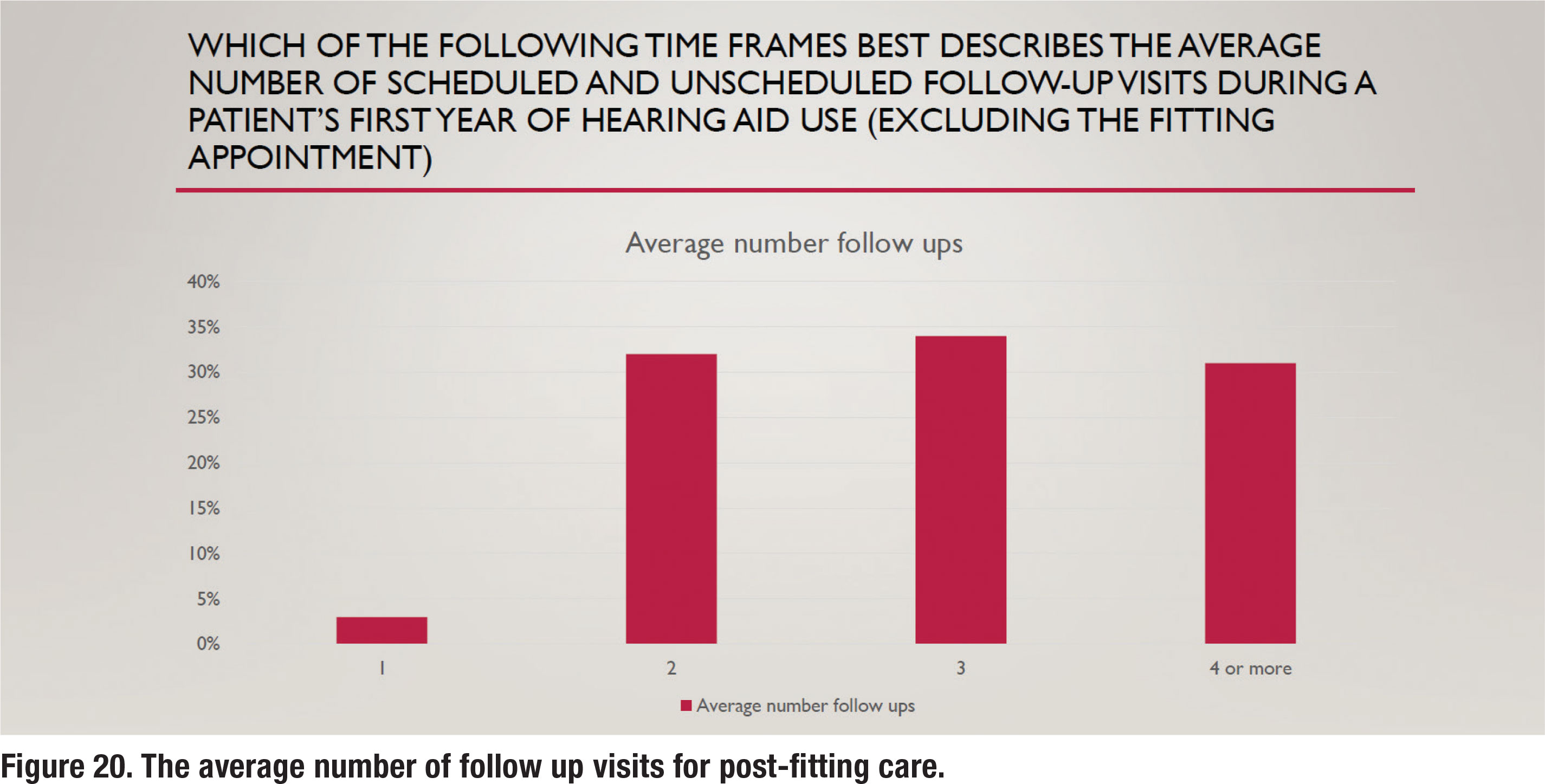

To better gauge the amount of time spent conducting follow up care, the respondents were also asked how many appointments, on average, were provided patients post-fitting. The results are illustrated in Figure 20. These results show a nearly even split between two, three and four or more follow-up visits. A previous survey from 12 years ago (Ramachandran et al 2012) indicated that about one-third of wearers fitted with hearing aids during the 1-year tracking period needed four or more follow-up visits. The results in Figure 20 are consistent with this finding, suggesting that recent approaches to improving efficiency such as telecare and the use of audiology assistants haven’t changed the number of follow up visits in an appreciable way.

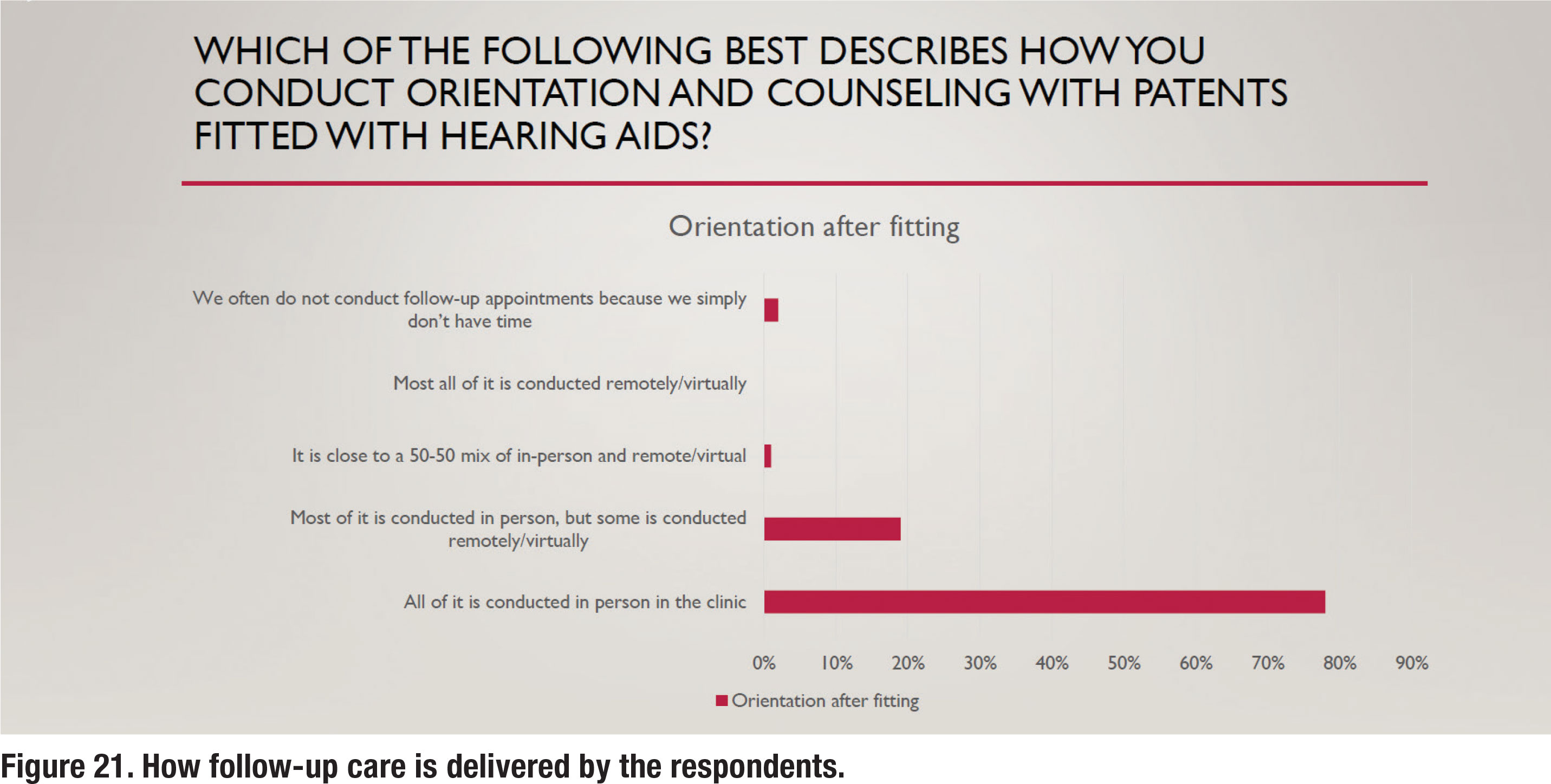

Use of Audiology Assistants and Telecare

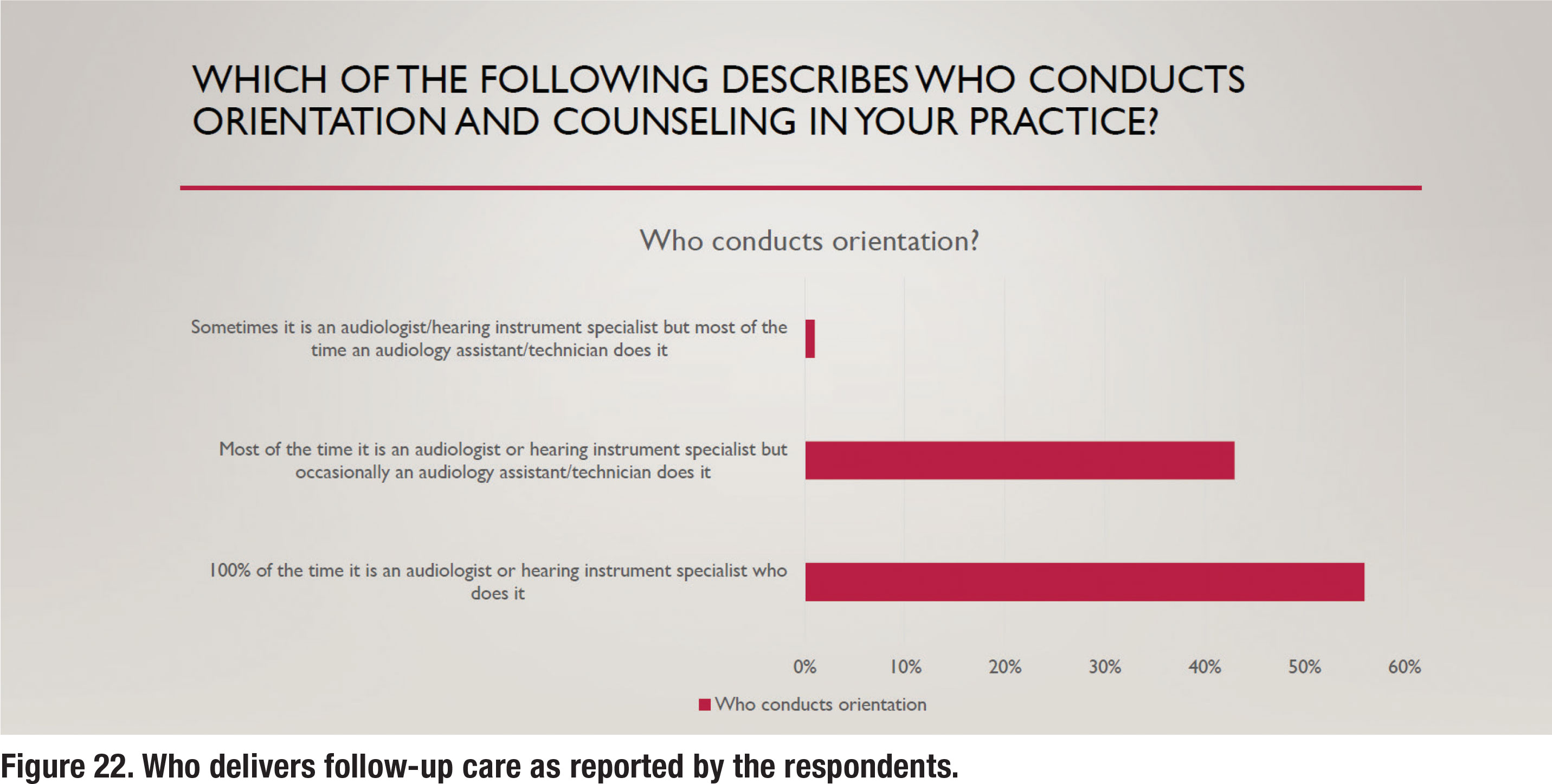

For the past several years both audiology assistants (technicians) and remote telecare options (tele-audiology) have been widely available to audiologists who want to utilize them to improve their clinical efficiency. Given the relatively large number of postfitting follow up visits (almost 75% of respondents reported three or more), it seems that the use of both telecare and audiology assistants would be popular. Results shown in Figure 21 and 22, however, suggest otherwise. Figure 21 shows that 98% of all or most follow up care is delivered in person rather than via telecare. Another recent trend is the use of audiology assistants who can be employed to perform many routine tasks and free up time for audiologists to see new patients. Several states now offer licensing or certification for audiology assistants. As Figure 22 illustrates, most or all follow up care is delivered by the audiologist, rather than a paraprofessional.

Considering that nearly 75% of patients are returning for three of more follow-up visits, and nearly all these follow-up visits are conducted in person by the audiologist, there is ample opportunity for practices to serve more patients through thoughtful division of labor. This is a common practice in the vision and dentistry professions but has yet to be widely embraced by audiologists.

Additionally, as the results of this survey indicate, follow-up care is rarely conducted via tele-audiology. Consequently, there is also ample opportunity to improve access to care by decreasing the burden associated with multiple in-person visits by using tele-audiology and other types of remote care. For help seeking individuals in need of hearing care, regardless of their location, tele-audiology has yet to be widely embraced as a means of reducing their travel burden for follow up care. Even after the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced most clinicians to rely on telecare for a year or more, the results of this survey suggest that audiologists have stopped relying on it and have instead migrated back to almost 100% of appointments conducted in person.

Conclusions: Are APSO Standards Moving the Needle on Popular Practices?

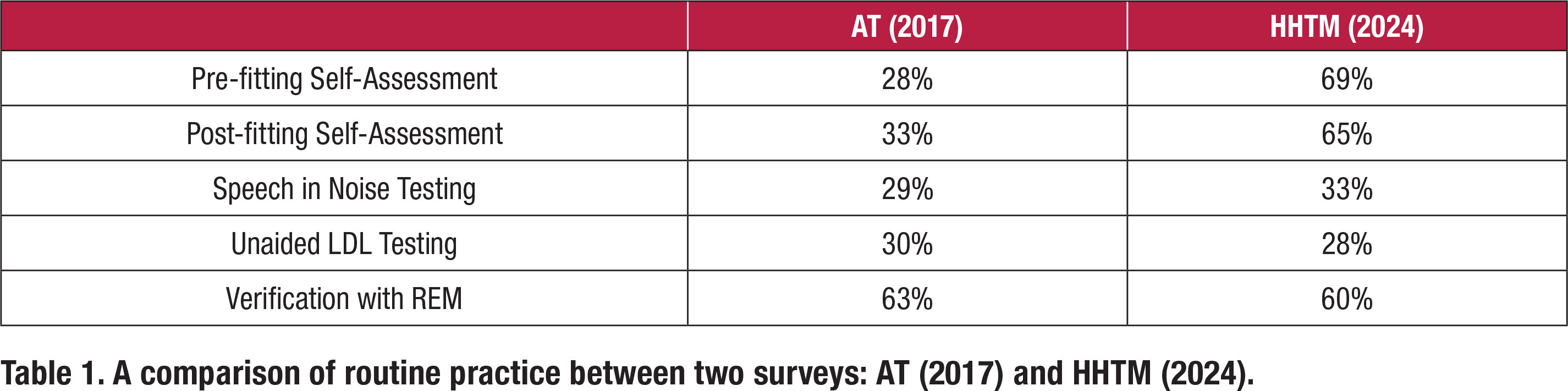

In 2017 John Greer Clark and colleagues conducted a similar online survey of 1,220 randomly selected members of the American Academy of Audiology which yielded only 88 responses. The results were published in the Dec/Nov 2017 issue of Audiology Today (Greer Clark, Huff and Earl, 2017). Table 1 compares results of their AT (2017) survey to the data reviewed in this article (HHTM 2024). Table 1 compares routine practice between the two surveys for five different clinical procedures that are part of the APSO S2.1 standard. The values in Table 1 were derived from the Top-2 Box scores in the two surveys for each of the five clinical procedures listed below.

For three of the five clinical procedures listed in Table 1, speech in noise testing, LDL measures and verification with REM, there is essentially no difference between the two surveys in the percentage of respondents reporting these as “routine practice.” In both surveys roughly one-third of respondents routinely conduct these measures. On the other hand, the more recent HHTM (2024) survey shows a rather dramatic increase in the number of respondents who report that they routinely conduct pre- and post- self-assessments.

It is difficult to explain why two common measures which are part of the APSO standard, pre- and post- fitting self-assessments, showed a dramatic increase between the surveys while the other three measures (speech in noise, LDLs and REM verification) did not. What has changed in seven years to warrant the sudden popularity of self-assessments? Perhaps self-assessments using validated self-reports are more readily available in hearing aid manufacturers’ fitting software, thus making the process easier to implement, or maybe third-party payers are requiring documentation of outcomes, driving the use of self-reports to higher levels.

The popularity of REM for verification also warrants further analysis. Note that both the AT (2017) and HHTM (2024) surveys indicate the use of REM as part of the verification process is popular. Both surveys indicate that 60% or more of respondents conduct REM. Some skepticism of this number is warranted for a couple of reasons. One, Mueller and Picou (2010) conducted a similar survey which indicated 40% of respondents routinely conduct REM. In their commentary they note this relatively low number has remained unchanged over the past 30 years. Two other questions in the HHTM (2024) survey, pertaining to REM, suggested that comprehensive use of REM is not popular. Although matching a prescriptive target might be popular practice today, measures such as REAR85 and RECD are not routinely conducted.

Finally, it is worth noting that response rates for the HHTM (2024) survey are remarkably low. The survey was emailed to 5,859 US-based audiologists, of which just 3% (186) completed the entire survey. Because the survey was 30 questions, those that responded dedicated the time and attention to detail to complete the rather long process of completing it — the same type of discipline required to implement new practice standards. For that reason, it is possible that the 3% of those who received the emailed survey are not a representative sample of typical rank and file audiologists and are more likely to actually follow practice standards.

Most audiologists, however, probably agree that best patient care is directly related to how decisions are made in the clinic. And these decisions, whenever possible, should be informed by the best available evidence that comes from research which is reflected in new clinical standards. As Greer Clark at al, (2017) stated, “Palmer (2009) points out that audiology’s code of ethics is clear that failure to follow best-practice guidelines is a violation of professional ethics. The continuation of inferior practice patterns that do not ensure best outcomes negatively impacts both patients and the profession. Patients expect that professionals are using the latest technologies and established best-practice protocols to ensure satisfactory outcomes.”

Since 2021, audiologists have had access to a new set of clinical standards for selecting and fitting hearing aids on adults. This current survey strongly suggests that a large gap, perhaps even a chasm, exists between access to the standards and actually implementing the standards. You don’t have to be an Einstein to see that what is popular practice is seldom best-practice. ■

The authors wish to thank Andy Bellavia of AuraFuturity for his thoughtful comments that contributed to our manuscript.

References

- Balling LW, Jensen NS, Caporali S, Cubick J, Switalski W. (2019). Challenges of instant-fit ear tips: What happens at the eardrum? Hearing Review. 26(12),12-15.

- Coverstone, J (2019). Why up-to-date practice standards for the profession of audiology are necessary. Hearing Review. Retrieved from https://hearingreview.com/practice-building/need-standards-audiology.

- Fitzgerald, M. B., Gianakas, S. P., Qian, Z. J., Losorelli, S., & Swanson, A. C. (2023). Preliminary Guidelines for Replacing Word-Recognition in Quiet With Speech in Noise Assessment in the Routine Audiologic Test Battery. Ear and Hearing, 44 (6), 1548–1561.

- Greer Clark, J., Huff, C., and Earl, B. (2017). Clinical Practice Report Card: Are We Meeting Best-Practice Standards for Adult Hearing Rehabilitation? Audiology Practices. 29(6),15-25.

- Guthrie, L. A., & Mackersie, C. L. (2009). A comparison of presentation levels to maximize word recognition scores. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20(6), 381–390.

- Hornsby, B., & Mueller, H.G. (2013). Monosyllabic word testing: Five simple steps to improve accuracy and efficiency. AudiologyOnline, Article #11978. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/

- Mueller H G, Stangl E, Wu Y-H. (2021) Comparing MPOs from six different hearing aid manufacturers: Headroom considerations. Hearing Review. 28(4):10-16.

- Mueller, H.G., Coverstone, J., Galster, J., Jorgensen, L., & Picou, E. (2021). 20Q: The new hearing aid fitting standard - A roundtable discussion. AudiologyOnline, Article 27938 Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Mueller, H.G., & Hornsby, B.W.Y. (2020). 20Q: Word recognition testing - let’s just agree to do it right! AudiologyOnline, Article 26478. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

- Mueller HG, Picou EM. (2010) Survey examines popularity of real-ear probe-microphone measures. Hear J 63(5),27–32. Palmer CV. (2009) Best practices: It’s a matter of ethics. Audiology Today 28(5), 30–35.

- Ramachandran V, Stach BA, and Schuette A. (2012). Factors Influencing Wearer Utilization of Audiologic Treatment Following Hearing Aid Purchase. Hearing Review. 19(02),18-29.

- Valente, M. (2006), Guideline for Audiologic Management of the Adult Patient. AudiologyOnline, Article 966. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline. com

Brian Taylor, Au.D. is senior director of audiology for Signia, and editor of Audiology Practices. He is a contributor to the HHTM Group and This Week in Hearing.

Kevin Liebe, Au.D. is president and CEO, HHTM Group, Hearing Health Matters, Inc., and Co-Creator and Producer, This Week in Hearing