How Do We Ensure Persons with Hearing Loss Get the Best Quality of Care?

Brian Taylor, Au.D.

It seems that a week doesn’t go by when yet another article is published demonstrating the association between hearing loss and other harmful conditions. Case in point, within a recent 10-day span, articles were published that continue to build a thorough evidence base indicating, 1.) Diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking are linked with hearing loss—and higher combinations of those risk factors increase the risk of hearing loss1, and 2.) hearing loss is a potential modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline.2

Collectively, this mounting evidence forms a nearly bulletproof case for early intervention in three ways: 1.) Improving overall wellness, particularly cardiovascular health, might prevent hearing loss, and 2.) Adults should have their hearing periodically checked beginning in middle age, and 3.) When necessary, should be fitted with hearing devices sooner, rather than later. Earlier audiological intervention is in the best interests of persons with hearing loss, their family, their employer, and their primary care physician and other medical staff that might work with them.

Despite the steady flow of peer reviewed research that one might think would prompt individuals into action, we continue to be faced with two uphill battles: 1.) The proverbial seven to 10-year wait persons with hearing loss tolerate from the moment they notice problems with their hearing until they seek a solution. A journey delayed as much or more by apathy and indifference than access to care and affordability of treatment.3 2.) The gap, actually more of a chasm, between knowledge and action – which is also, in large part, driven by apathy and indifference.4 Recent estimates suggest there is a 17-year gap between when new research findings are published and when those findings move the needle on decision-making in the clinic.5 That 17-year gap applies to general medicine, but it’s not hard to see it in our own profession. There is no shortage of innovative interventions and diagnostic approaches, with research supporting their effectiveness, which have failed to be embraced by most clinicians. The 60-60 criteria for cochlear implant candidacy, use of speech in noise testing, matching a validated prescription gain target — the adherence to modern audiology protocols in clinical practice is concerningly low. And there is no reason to believe that newer tools like extended high frequency audiometry, remote finetuning and automated audiometry, even after sizable amounts of evidence is published supporting their use, won’t follow the same path of low adherence.

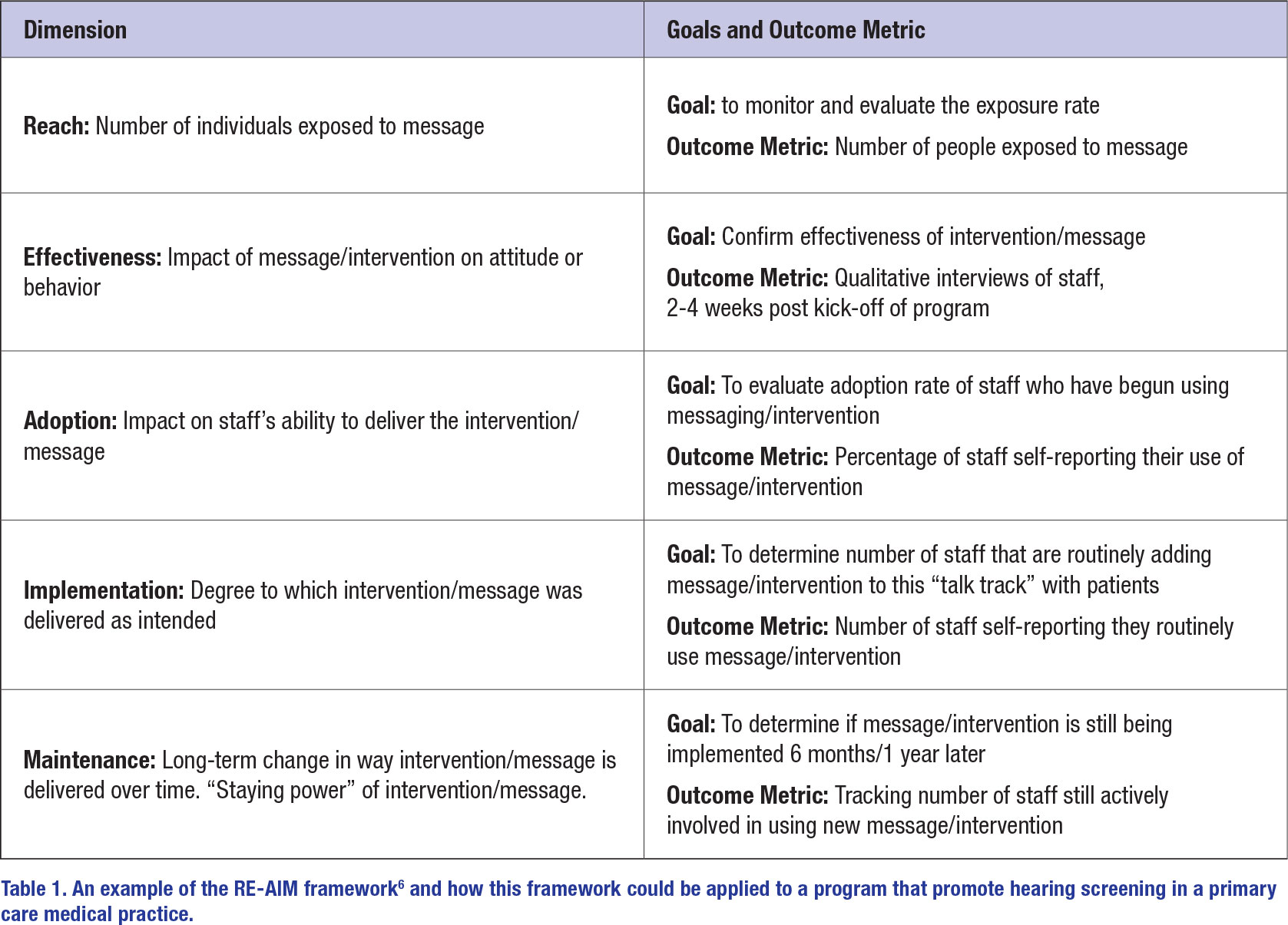

What’s driving this knowledge-doing gap? More than 20 years ago an academic field, known as implementation science, emerged that attempts to understand the chasm between what clinicians might know and what they actually do. Since that time, several academic centers including those at the University of Washington and Washington University in St. Louis have established departments devoted to the study of implementation science with the basic goal of narrowing the time between the creation of new scientific knowledge and when it is applied in the clinic. The overarching goal of implementation science is to bring about the best possible care for everyone. Implementation scientists have developed several interesting models, including what’s called the RE-AIM framework, summarized in Table 16. It is a systematic, five-step approach designed to speed the process of changing behaviors – both of the clinician, and in-turn, the patient. One ideal place to put implementation science to work is getting more primary care physicians and nurse practitioners, the front-line professionals who routinely interact with middle aged and older adults (those most prone to the consequences of untreated hearing loss) more actively involved in promoting the benefits of routine hearing screening and early intervention strategies.

Table 1 below outlines a hypothetical example of how the RE-AIM framework could be applied when an audiology practice partners with a local medical practice, comprised of several nurse practitioners and primary care physicians. In this example, the audiology practice is providing messaging collateral to the medical practice that promotes the importance of routine hearing screening for all adults aged 50 years and older. The vehicle for delivering this message could be posters that hang in exam rooms, brochures handed to patients and videos that play on the TV in the reception area. The core message would be along the lines of “The sooner we treat hearing loss, the better the outcome – it all starts with a quick, routine hearing check. We can do the hearing check here, right now and you will know your hearing number.”* Additionally, “Hearing better can make you think/socialize/ connect with others better” would be a key part of the communication strategy — a constructive message that minimizes harm while motivating people to act.7

* see https://hearingnumber.org/what-is-the-hearing-number/

One can easily imagine how these types of frameworks can be applied to audiology so that persons with hearing loss receive appropriate interventions, earlier. Although there are dozens of papers in our profession devoted to translational research, there appear to be just a handful of papers on the broader topic of implementation science.8,9 Now is the time for that to change. The RE-AIM framework, if applied to speeding the journey of hearing care, tells us that reducing apathy and indifference toward hearing loss and treatment is a methodical process that requires careful planning, creative thinking, imaginative messaging and systematic monitoring of outcomes for each of the five stages shown in Table 1. Decades of research demonstrating the co-morbid nature of hearing loss tells us that the sooner we treat, the better the outcome. Speeding the journey toward hearing loss awareness, acceptance and treatment just might start with closing the gap between what clinicians know and what they do. Shortening the knowledge-doing gap will likely narrow the journey from apathy to action for persons with hearing loss. ■

References

- Mick, Paul Thomas; Kabir, Rasel; Pichora-Fuller, Margaret Kathleen; Jones, Charlotte; Moxham, Lindy; Phillips, Natalie; Urry, Emily; Wittich, Walter. Associations Between Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Audiometric Hearing: Findings From the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Ear and Hearing. May 01, 2023. Published ahead of print.

- An YY, Lee ES, Lee SA, et al. Association of Hearing Loss With Anatomical and Functional Connectivity in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment [published online ahead of print, 2023 May 11]. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023.

- Carlson ML, Nassiri AM, Marinelli JP, Lohse CM, Sydlowski SA; Hearing Health Collaborative. Awareness, Perceptions, and Literacy Surrounding Hearing Loss and Hearing Rehabilitation Among the Adult Population in the United States. Otol Neurotol. 2022;43(3):e323-e330.

- Sydlowski SA, Marinelli JP, Lohse CM, Carlson ML; Hearing Health Collaborative. Hearing Health Perceptions and Literacy Among Primary Healthcare Providers in the United States: A National Cross-Sectional Survey. Otol Neurotol. 2022;43(8):894-899

- Rubin R. It Takes an Average of 17 Years for Evidence to Change Practice-the Burgeoning Field of Implementation Science Seeks to Speed Things Up. JAMA. 2023;329(16):1333-1336.

- Estabrooks PA, Gaglio B, Glasgow RE, et al. Editorial: Use of the RE-AIM Framework: Translating Research to Practice With Novel Applications and Emerging Directions. Front Public Health. 2021;9:691526. Published 2021 Jun 11.

- Blustein J, Weinstein BE, Chodosh J. It is time to change our message about hearing loss and dementia [published online ahead of print, 2023 Apr 3]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;10.

- Szczepek AJ, Domarecka E, Olze H. Translational Research in Audiology: Presence in the Literature. Audiol Res. 2022;12(6):674-679. Published 2022 Nov 28.

- Studts CR. Implementation Science: Increasing the Public Health Impact of Audiology Research. Am J Audiol. 2022;31(3S):849-863