Reversing the Downhill Effects of Apathy and Indifference

Brian Taylor, Au.D.

Although the results of the ACHIEVE randomized controlled trial, which demonstrated hearing aid use slows down cognitive decline in an at-risk population, generated many headlines in the professional publications over the summer, we cannot forget untreated hearing loss is also associated with an increased risk of falling, depression, social isolation, poorer mobility, under employement, and reduced quality of life. Not to mention the impact of untreated hearing loss on daily communication and the negative effects it has on relationships with family, friends and colleagues. These are all great reasons for audiologists to be actively involved in hearing screening programs that are conducted on healthy middle-aged and older adults.

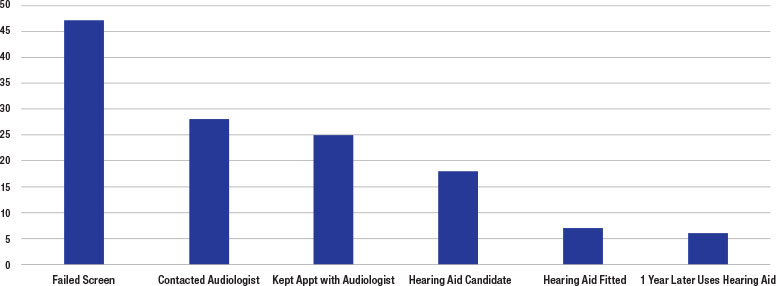

The downward sloping pattern in Figure 1 reflects a pattern found in several recent studies that have investigated the effectiveness of hearing screening programs: Even when primary care physicians take an active role in the hearing screening process, most individuals who fail the screen are not fitted with hearing aids. As Figure 1 shows, at each stage of the journey, a substantial number of individuals with hearing loss fail to take the necessary actions toward treatment. As illustrated in Figure 1, starting with a large pool of middle-aged and older adults who failed the hearing screening (just under 50% of the total group screened), a mere 10 to 15% of them acquired hearing aids and used them.

It’s important to note the trend shown in Figure 1 represents a sort of best-case scenario in which physicians were actively involved in the screening program. In many of the studies there was also a control group who did not receive a hearing screening or an educational intervention that might have motivated someone into action. A considerably smaller percentage of that control group than what is depicted in Figure 1 consulted with an audiologist and eventually acquired hearing aids.

Figure 1. A summary of key findings in recent studies on the effectiveness of hearing screening programs on middle-aged and older adults. See references for list of studies summarized here.

One recent study is especially relevant. Smith et al (2023) compared hearing screening conducted in the clinic with encouragement from a primary care physician to two additional groups: One group completed hearing screening at-home with encouragement from a primary care physician and the other group also completed screening at home but without encouragement from the doctor. Their results showed that offering encouragement and screening in the clinic led to significantly higher rates of patients following the provider’s recommendations for further follow-up. However, encouragement from the primary care provider for the at-home screening did not improve adherence to follow-up recommendations. It seems the simple act of encouraging people to get screened must be combined with completing the screening in the clinic for the program to be most effective.

Shoring Up the Leaks

What do these results and the downward slope in Figure 1 mean for business-minded clinical audiologists?

- Build strong relationships with medical gatekeepers and encourage them to provide in-person hearing screenings. Given the added costs associated with establishing an in-clinic hearing screening program, audiologists should be willing to advise primary care providers on cost-effective strategies for setting up these programs. Specifically, the results from Smith et al (2023) indicate that in-clinic hearing screening is more effective than screenings conducted at home.

- Be a trusted referral source. Considering that about half of all individuals who fail an initial screening do not contact an audiologist, make sure that patients know you exist and that your primary role is to educate them and gather more detailed information about their hearing loss – not sell them hearing aids.

- Dispense and service over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids. The results of the studies, summarized in Figure 1, show that when physicians and other medical gatekeepers are actively involved in the hearing screening program - even when conducting the screening in-person in their clinic -- most individuals who fail the screening will eventually fall through the cracks. There are probably several reasons for this, but at the top of the list must be apathy and indifference on the part of both the person with hearing loss and the medical gatekeeper. By dispensing OTC hearing aids – either in your clinic or on your website – and servicing (for a fee) OTCs bought elsewhere, you are providing additional consumer choice that could break the cycle of apathy and indifference surrounding hearing loss. ■

References

- Dubno JR, Majumder P, Bettger JP, et al. A pragmatic clinical trial of hearing screening in primary care clinics: cost-effectiveness of hearing screening. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2022;20(1):26.

- Folmer RL, Saunders GH, Vachhani JJ, et al. Hearing Health Care Utilization Following Automated Hearing Screening. J Am Acad Audiol. 2021;32(4):235-245

- Smith SL, Francis HW, Witsell DL, et al. A Pragmatic Clinical Trial of Hearing Screening in Primary Care Clinics: Effect of Setting and Provider Encouragement [published online ahead of print, 2023 Aug 21]. Ear Hear. 2023;10.

- Yueh B, Collins MP, Souza PE, et al. Long-term effectiveness of screening for hearing loss: the screening for auditory impairment-which hearing assessment test (SAI-WHAT) randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(3):427-434.

- Zazove P, Plegue MA, McKee MM, et al. Effective Hearing Loss Screening in Primary Care: The Early Auditory Referral-Primary Care Study. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(6):520-527.