The Slow Progression of Research in a World of Constant Product Launches

Brian Taylor, Au.D.

In the early 1990’s, the late Scottish researcher Stuart Gatehouse published data showing speech recognition ability in noise, although initially stable in the first days of a fitting, continued to improve as the individual continues to wear their devices. His work demonstrated improvements in speech understanding in noise continued to improve over a period of six to 12 weeks after the initial fitting for some individuals.

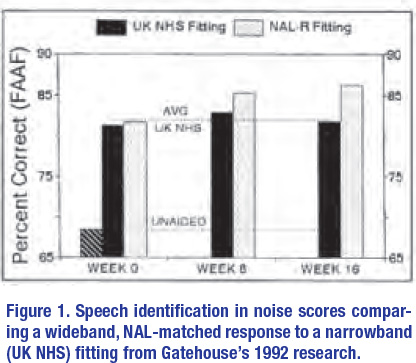

Importantly, these improvements in speech recognition over time tended to occur in individuals fitted with wideband hearing aids, matched to a NAL target. Results of one of Gatehouse’s acclimatization studies are shown in Figure 1. Note that differences in performance between the wideband NAL and the narrowband “first fit” fittings started to become apparent at six weeks post fitting. Also note his results for the narrowband fitting plateaued at six weeks, while the wideband NAL fitting showed continued, gradual improvement between six- and 12-weeks post-fitting. Although hearing aid processing has become more sophisticated over the past 30 years, there is good reason to believe that a high percentage of hearing aids fitted today resemble the narrowband “first-fit” used in Gatehouse’s research; thus, patients fitted with the narrow-bandwidth device might be at-risk for poorer than expected speech understanding results – even after several weeks of hearing aid use. In contrast, patients fitted with the wideband, NAL-matched devices, and given ample time to acclimatize to them, are likely to benefit from the guidance of an audiologist who understands the time course associated with “getting used” to new sounds.

Gatehouse’s findings—that a NAL-matched, wideband response yielded gradual speech understanding improvements that didn’t become evident until six to 12 weeks post-fitting and that a narrowband hearing aid failed to do this — were not lost to history. Around the time these two studies were published, Mead Killion created the mythical Dr. ABONSO avatar to help bring the effects of acclimatization to life for clinicians. Dr. ABONSO (an acronym that stands for Automatic Brain-Operated Noise Suppressor Option) coined the term Hearing Aid Brain Rewiring Accommodation Time or HABRAT to describe this phenomenon. Killion and Gatehouse, in fact, went to great lengths to state that HABRAT was more than merely “getting used” to hearing aids. HABRAT is a fundamental perceptual process in which hearing aid wearers are, when exposed to new speech information through their recently fitted devices, need considerable time to learn to make use of the new speech cues to eventually optimize benefit. In a 1993 article published in Hearing Instruments, Killion and Gatehouse asserted that the brain is plastic and needs time to rewire to the new sound inputs.

Gatehouse’s findings—that a NAL-matched, wideband response yielded gradual speech understanding improvements that didn’t become evident until six to 12 weeks post-fitting and that a narrowband hearing aid failed to do this — were not lost to history. Around the time these two studies were published, Mead Killion created the mythical Dr. ABONSO avatar to help bring the effects of acclimatization to life for clinicians. Dr. ABONSO (an acronym that stands for Automatic Brain-Operated Noise Suppressor Option) coined the term Hearing Aid Brain Rewiring Accommodation Time or HABRAT to describe this phenomenon. Killion and Gatehouse, in fact, went to great lengths to state that HABRAT was more than merely “getting used” to hearing aids. HABRAT is a fundamental perceptual process in which hearing aid wearers are, when exposed to new speech information through their recently fitted devices, need considerable time to learn to make use of the new speech cues to eventually optimize benefit. In a 1993 article published in Hearing Instruments, Killion and Gatehouse asserted that the brain is plastic and needs time to rewire to the new sound inputs.

When the HABRAT principle was published thirty years ago, there was no direct physiologic evidence of cortical changes in the brain associated with properly fitting hearing aids on individuals with sensorineural hearing loss. Gatehouse and Killion did, however, surmise that because of the lack of stimulation associated with sensorineural hearing loss, the brain begins to allocate surrounding areas to those unstimulated regions. Recent research confirms what Gatehouse deduced in the early 1990’s: the human adult auditory system is indeed plastic.

Re-purposing and Reversing Auditory Cortical Function

Recently, Anu Sharma and colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder have demonstrated that the adult auditory cortex is a highly adaptive system that re-organizes itself quickly in response to changing inputs. Known as neuroplasticity, the capacity for the human auditory system to adapt to changes results from several factors including learning, maturation, injury, disease, sensory stimulation, and sensory deprivation. (A June 2021 20Q article at Audiology Online is probably the most assessable entry point into Sharma’s work).

Their work has shown that the cortex of individuals with hearing loss exhibit signs of cross-modal plasticity in which portions of a damaged auditory region of the brain are taken over by unaffected regions. Stated differently, when a peripheral hearing loss deprives the auditory cortex of sound stimulation, other areas of the brain commandeer that area and repurpose that cortical space for other activities. Using cortical evoked potentials, Sharma and colleagues have shown there is a physiologic basis for the laboratory findings, surmised by Gatehouse thirty years ago. Importantly, their research shows that with proper stimulation the effects of cross-modal plasticity can be reversed. These cross-modal neuroplastic effects seem to occur in all individuals with hearing loss even those with mild hearing loss, including persons who do not self-report hearing loss.

Further, the key to reversing these effects with amplification appears to be a properly fitted hearing aid, as those who were underfitted tended to not see the same improvement compared to those who were properly fitted. Another task that requires the expertise of an audiologist who ensures gain targets are met and the time course to acclimatization is well-understood by the patient. Cross-modal plasticity and the role of the audiologist in optimizing benefit speaks to the value of the audiologist throughout the treatment process — a critical point as over-the-counter devices loom. It also speaks to the fact that gathering a complete picture of hearing loss and its consequences is a continual work-in-progress in which information is pieced together over decades. A notion that is often lost in a profession that launches new hearing aid products and features about every six months. ■