To Boost Outcomes for Hearing Aid Wearers, the Profession Should Commit to Telehealth Services

Brian Taylor, Au.D.

It should concern every audiologist that anywhere from 5 percent to one-quarter of patients never use their hearing aids. Or that by some accounts, an astounding 98 percent of hearing aid owners say they had at least one problem with their hearing aids in the first year. Or that 54 percent of problems go unreported to HCPs, and 46 percent remain unresolved even after seeing an HCP.

I think we can all agree, such findings indicate that the hearing patient journey, at least for some, can be complex, and has room for improvement.

All this is happening at a time when more people are seeking the services of an audiologist. Not only do 20 percent of people aged 60 or older suffer disabling hearing loss, but up to 18 percent of U.S. adults self-report communication difficulties despite normal audiograms.

And many of the latter are apparently looking for help. In a recent survey of more than 200 audiologists, 68 percent reported seeing individuals with self-reported communication difficulties but normal hearing. We know that people with mild hearing loss don’t usually acquire hearing aids, so it’s fair to assume those with subclinical hearing loss rarely seek assistance, even though today’s advanced hearing aids could enhance their ability to communicate in a variety of situations.

Whatever we’re doing—and however we’re doing it—there continue to be unaddressed gaps in hearing aid usage and overall adoption. If people are going to get the hearing care they need, we must make it easier for them to adopt hearing aids. The profession (audiologists) and industry (hearing aid manufacturers) must work in partnership to find ways to solve both wear-time and uptake problems.

High-quality, regulated devices in a range of price points and form factors are, of course, part of the solution. But we should employ another important strategy if we’re to expand the market and improve hearing aid wear-time: widescale embrace of telehealth services in audiology.

Growing Acceptance

In April, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services acknowledged the importance of telehealth in delivering audiology services by significantly expanding the number of telehealth services that audiologists could bill directly to Medicare during the current public health emergency. The Department of Veterans Affairs has long pursued innovative ways of delivering hearing care to veterans living far from VA facilities, including through telehealth audiology. And today, most states now allow licensed audiologists to offer telehealth services.

For a variety of reasons—some brought into stark relief by the Covid-19 pandemic—ongoing telehealth will prove important to delivering hearing care. It will also help address aspects of the hearing patient journey that might otherwise hinder hearing aid use and uptake. As a member of the HIA’s Telehealth Task Force, I encourage professional and industry organizations to endorse telehealth options, establish best practices, and set us on a path toward vastly improved hearing outcomes through the acceptance and promotion of telehealth services.

Telehealth at large has already begun to prove its value. When the Covid-19 pandemic struck, healthcare providers and their patients were urged to adopt telehealth services—care provided virtually, at a distance, via telephone or computer-based videoconferencing software. According to recent analysis by McKinsey & Company, telehealth utilization spiked in spring 2020 and has now leveled off at 38 times what it was before the pandemic. This would indicate a positive, long-term shift in healthcare delivery. Today, McKinsey & Company reports 13 to 17 percent of all office and outpatient visits, across all tracked specialties, are telehealth visits. Moreover, researchers see skyrocketing investment in virtual care.

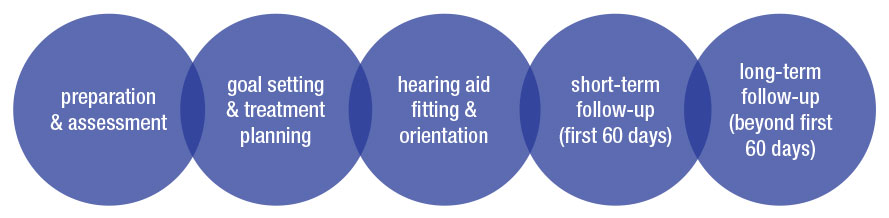

Now consider hearing health, specifically. The patient journey toward better hearing can be time-consuming. Each of the pictured five key steps has traditionally required at least one in-person visit with an HCP, taking an average of 30 to 60 minutes of facetime, not including travel. By enabling the patient and HCP to pick and choose when and how they interact, telehealth has the potential to empower the patient to become a more effective hearing aid wearer over the long haul

Promising Developments

Already, the industry is identifying ways to implement telehealth successfully. At Signia (my day job) we’ve spent several years developing telehealth solutions designed to help audiologists engage remotely with their patients after the initial inoffice fitting, including remote tuning, troubleshooting, and video calls. Other manufacturers have invested similarly in telehealth. All of these investments further the patient-provider partnership – even after COVID-19 is in our rear view mirror.

Although a telehealth model is not for everyone—some patients may not be comfortable with technology while others simply prefer face-to-face care—we’re reaching a point when a permanent, full-time telehealth option is not just viable, but also critical to the growing need for better hearing.

It’s been shown in other specialties that when given a choice, many patients prefer a telehealth option, especially for routine appointments. And increasingly, older adults—many of whom would benefit from hearing aids—have shown they’re comfortable with the technology needed for telehealth. They’ve used online tools to connect with family and friends during a pandemic; now, recognizing the convenience, many are willing and able to try telehealth when offered the tools.

Not every element of in-person hearing care can be delivered virtually (yet), but enough of the patient journey can be achieved via computer or smartphone that when both patient and audiologists agree to it, telehealth should be used whenever possible. Audiologists are trained to follow the science, and in the case of telehealth, the science shows that under the right circumstances, it is a viable, important, and effective tool for improving uptake and outcomes. ■

References

- Aazh, H., Prasher, D., Nanchahal, K., & Moore, B. C. (2015). Hearing- aid use and its determinants in the UK National Health Service: a cross-sectional study at the Royal Surrey County

- Solheim, J., & Hickson, L. (2017). Hearing aid use in the elderly as measured by datalogging and self-report. International Journal of Audiology, 56(7), 472–479

- Bennett, R. J., Kosovich, E. M., Stegeman, I., Ebrahimi-Madiseh, A., Tegg-Quinn, S., & Eikelboom, R. H. (2020). Investigating the prevalence and impact of device-related problems associated with hearing aid use. International Journal of Audiology, 59(8), 615–623.

- Bennett, R.J. (2021) Underreported hearing aid problems: No News is good news, right? Wrong! Hearing Journal Feb 16-18.

- Tremblay, K. L., Pinto, A., Fischer, M. E., Klein, B. E., Klein, R., Levy, S., Tweed, T. S., & Cruickshanks, K. J. (2015). Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties Among Adults With Normal Audiograms: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Ear and Hearing, 36(6), e290–e299.

- Koerner, T., Papesh, M., & Gallun, F. (2020). Questionnaire survey of current rehabilitation practices for adults with normal hearing sensitivity who experience auditory difficulties. AJA. 29:738-761.