Fitting Low-Gain Hearing Aids on Adults with Normal Audiograms and Self-reported Hearing Difficulties: Opportunity or Threat?

Brian Taylor, Au.D.

1 — A Common Scenario

A middle-aged person has arrived at your clinic for a routine hearing assessment. During the case history he states that he has struggled with communicating in background noise for more than a decade.

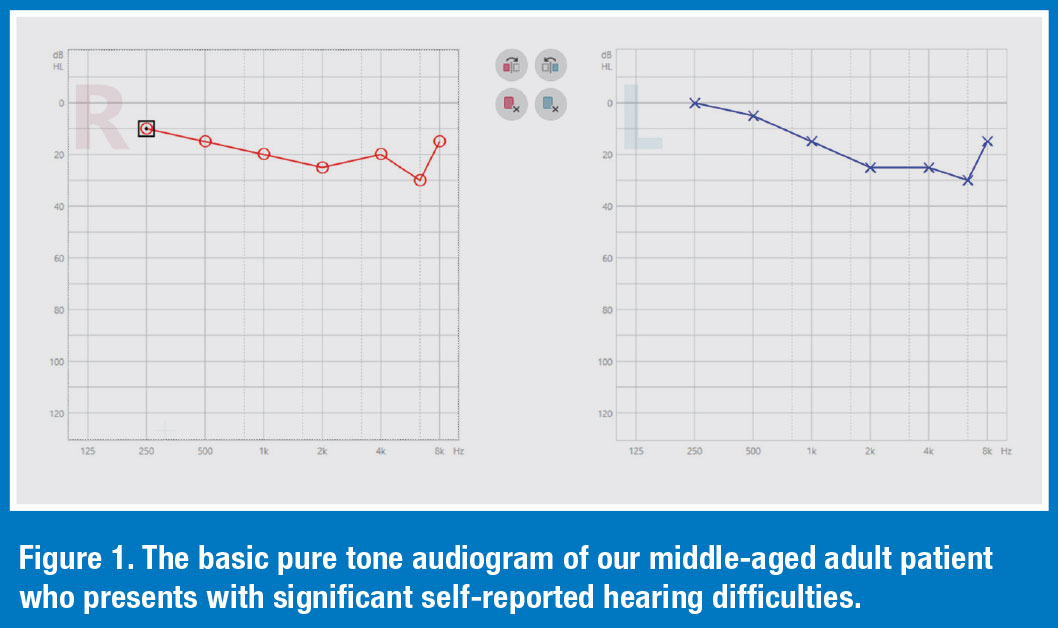

Although he has no other symptoms or complaints that would warrant a referral to an otolaryngologist, he does vociferously complain that his communication ability is progressively worsening, and he is beginning to feel frustrated and annoyed during social and workplace situations when there is a lot of noise and reverberation. Your routine audiological assessment indicates no medical complications. In fact, the basic air conduction, pure tone audiogram, shown in Figure 1, is within the traditional range of normal hearing (<20 dB HL, pure tone average). Other tests, such as word recognition and immittance audiometry are completely within the normal range.

Although he has no other symptoms or complaints that would warrant a referral to an otolaryngologist, he does vociferously complain that his communication ability is progressively worsening, and he is beginning to feel frustrated and annoyed during social and workplace situations when there is a lot of noise and reverberation. Your routine audiological assessment indicates no medical complications. In fact, the basic air conduction, pure tone audiogram, shown in Figure 1, is within the traditional range of normal hearing (<20 dB HL, pure tone average). Other tests, such as word recognition and immittance audiometry are completely within the normal range.

- Source: Koerner, T., Papesh, M., & Gallun, F. (2020). Questionnaire survey of current rehabilitation practices for adults with normal hearing sensitivity who experience auditory difficulties. AJA. 29:738-761

2 — Hearing Thresholds Through the Lifespan

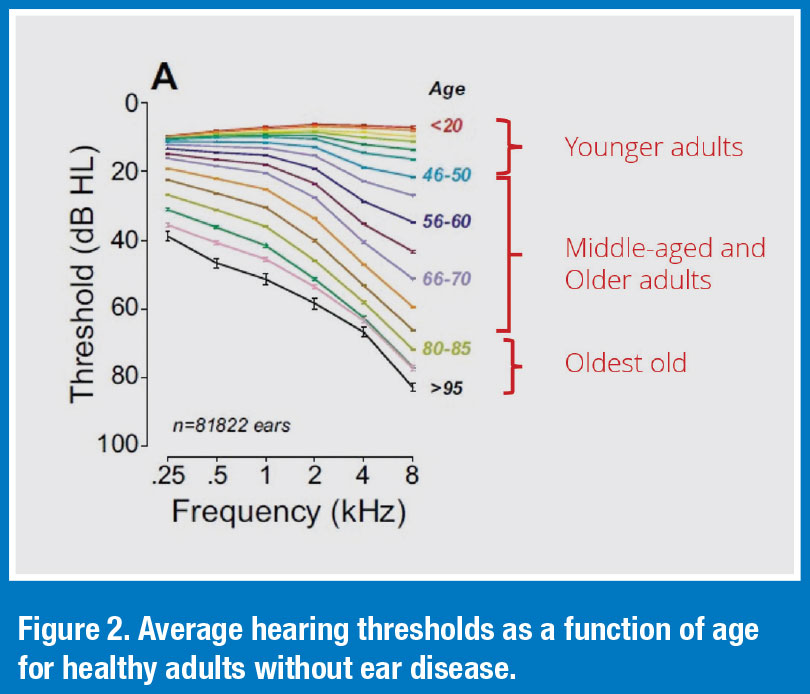

Figure 2 illustrates that typical decline in hearing thresholds associated with the normal aging process. Note that hearing thresholds in the high frequencies, on average, do not dip below 20dB HL until a person is well into their sixth decade of life. The decline is hearing thresholds through the lifespan, as they are charted on the routine audiogram in Figure 2, do not explain the self-reported hearing difficulties of younger and middle-aged adults who may present in your clinic with significant communication difficulties, particularly in acoustically challenging situations, and normal hearing thresholds through 8000 Hz.

Figure 2 illustrates that typical decline in hearing thresholds associated with the normal aging process. Note that hearing thresholds in the high frequencies, on average, do not dip below 20dB HL until a person is well into their sixth decade of life. The decline is hearing thresholds through the lifespan, as they are charted on the routine audiogram in Figure 2, do not explain the self-reported hearing difficulties of younger and middle-aged adults who may present in your clinic with significant communication difficulties, particularly in acoustically challenging situations, and normal hearing thresholds through 8000 Hz.

- Source: Grant, K. J., Parthasarathy, A., Vasilkov, V., Caswell-Midwinter, B., Freitas, M. E., de Gruttola, V., Polley, D. B., Liberman, M. C., & Maison, S. F. (2022). Predicting neural deficits in sensorineural hearing loss from word recognition scores. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 8929.

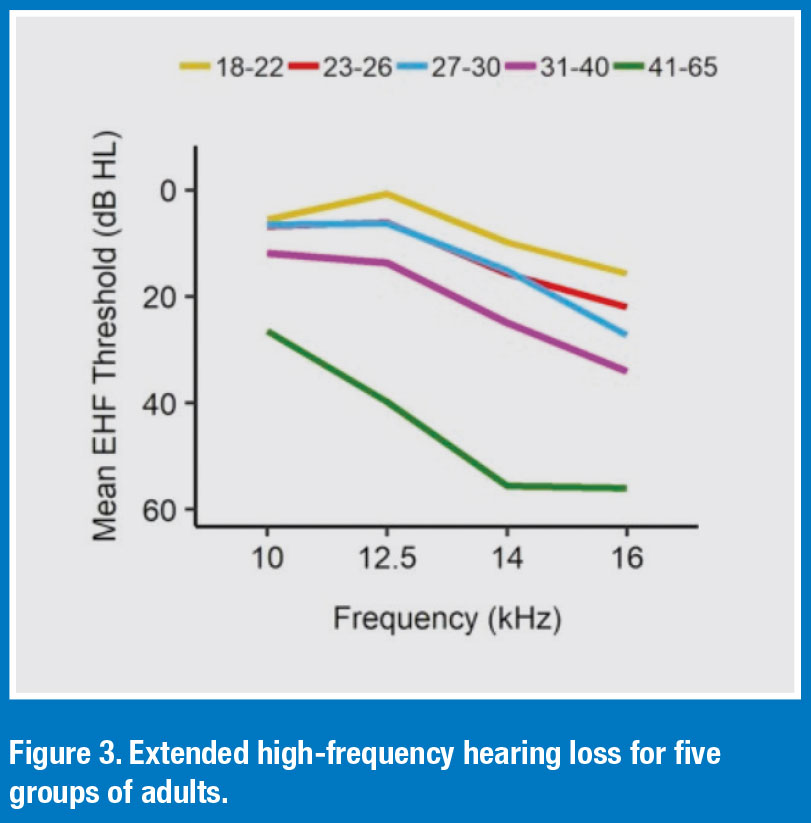

Recent studies using distortion-product otoacoustic emissions (DPOEs) and extended high-frequency audiometry indicate age-related changes occur in the cochlea as early as the third decade of life. These age-related changes in extended high frequency hearing are illustrated in Figure 3. This data, pooled across five age cohorts, indicate high-frequency hearing loss begins to appear on extended high-frequency audiometry as early as a person’s late-20s. Additionally, these changes accelerate over the next twenty years and may not show up on a conventional hearing test until age 50 or older.

Recent studies using distortion-product otoacoustic emissions (DPOEs) and extended high-frequency audiometry indicate age-related changes occur in the cochlea as early as the third decade of life. These age-related changes in extended high frequency hearing are illustrated in Figure 3. This data, pooled across five age cohorts, indicate high-frequency hearing loss begins to appear on extended high-frequency audiometry as early as a person’s late-20s. Additionally, these changes accelerate over the next twenty years and may not show up on a conventional hearing test until age 50 or older.

- Source: Motlagh Zadeh, L., Silbert, N. H., Sternasty, K., Swanepoel, W., Hunter, L. L., & Moore, D. R. (2019). Extended high-frequency hearing enhances speech perception in noise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(47), 23753–23759

3 — A Condition that Goes by Many Names

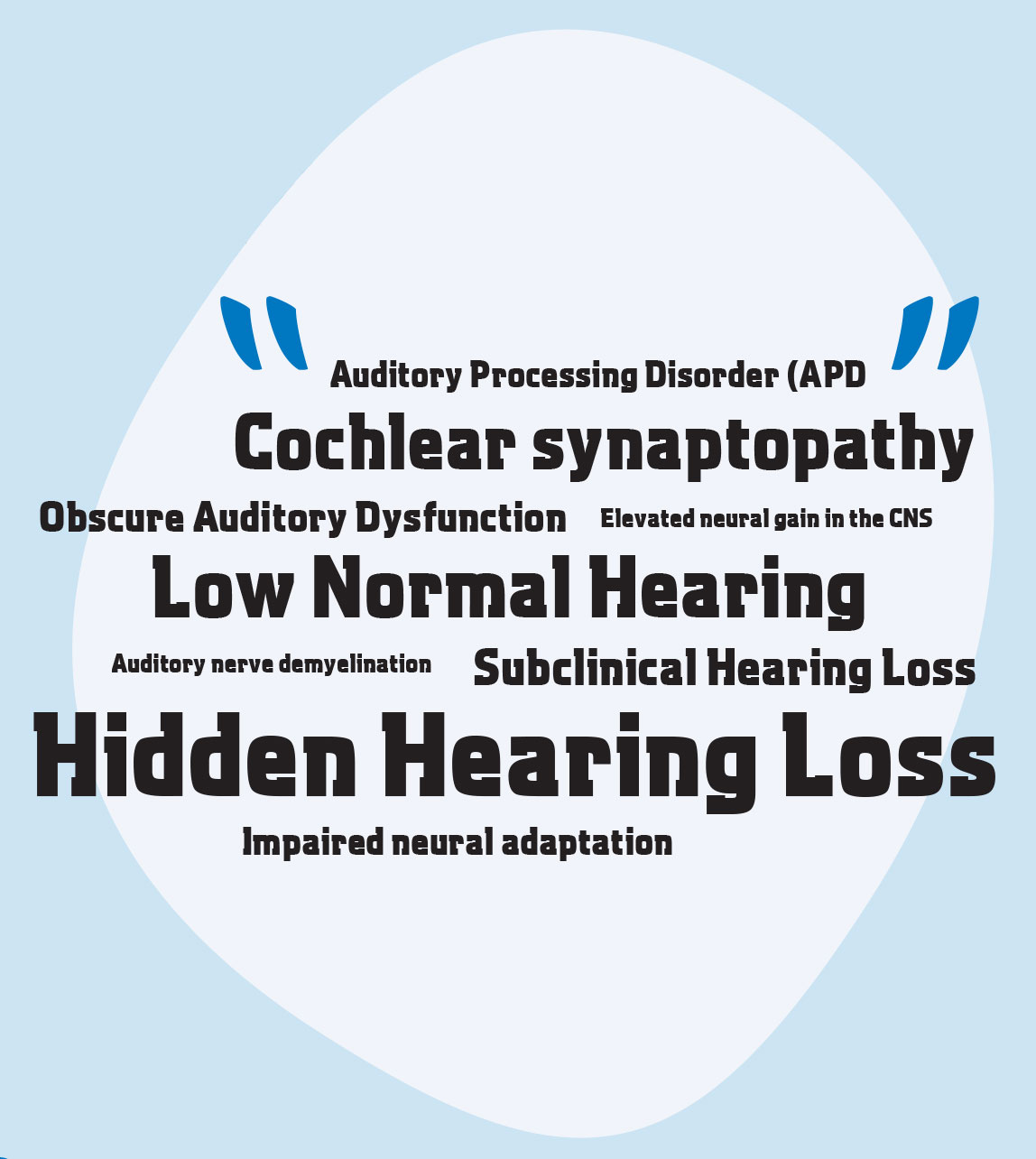

All these terms have been used to describe the adult, often young to middle-aged, who presents in the clinic with self-reported hearing difficulties and a normal routine audiogram. Although it might be tempting to label these individuals with APD, according to American Academy of Audiology (AAA) guidelines, an APD diagnosis requires an individual perform at two standard deviations below the mean in at least one ear on two or more behavioral auditory tests. Since the profession lacks a clear consensus on what APD tests should be part of an assessment battery, it is extremely difficult to make a definite APD diagnosis. Consequently, these other terms are often used to describe the condition.

All these terms have been used to describe the adult, often young to middle-aged, who presents in the clinic with self-reported hearing difficulties and a normal routine audiogram. Although it might be tempting to label these individuals with APD, according to American Academy of Audiology (AAA) guidelines, an APD diagnosis requires an individual perform at two standard deviations below the mean in at least one ear on two or more behavioral auditory tests. Since the profession lacks a clear consensus on what APD tests should be part of an assessment battery, it is extremely difficult to make a definite APD diagnosis. Consequently, these other terms are often used to describe the condition.

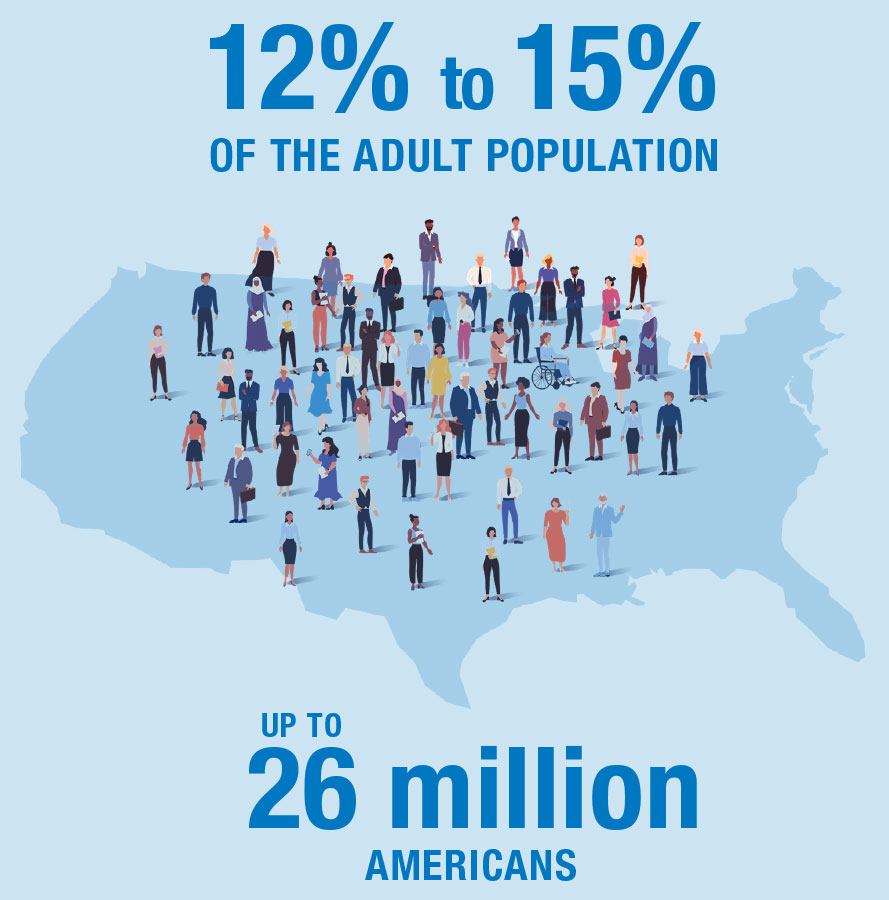

4 — Prevalence of the Condition

Given the subjective nature of quantifying selfreported hearing difficulties, it is tough to know exactly how many individuals experience this condition. However, two separate studies provide some insights. In one study involving 2783 participants with normal audiograms, Tremblay, et al (2015) reported that 12.0% had self-reported hearing difficulties. Another study with 2176 participants, Spankovich et al (2018) indicated that 15.0% had normal hearing through 8000 Hz accompanied with self-reported hearing difficulties.

Given the subjective nature of quantifying selfreported hearing difficulties, it is tough to know exactly how many individuals experience this condition. However, two separate studies provide some insights. In one study involving 2783 participants with normal audiograms, Tremblay, et al (2015) reported that 12.0% had self-reported hearing difficulties. Another study with 2176 participants, Spankovich et al (2018) indicated that 15.0% had normal hearing through 8000 Hz accompanied with self-reported hearing difficulties.

- Source: Sources: Spankovich, C., Gonzalez, V. B., Su, D., & Bishop, C. E. (2018). Self reported hearing difficulty, tinnitus, and normal audiometric thresholds, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Hearing Research, 358, 30–36.

- Tremblay, K. L., Pinto, A., Fischer, M. E., Klein, B. E., Klein, R., Levy, S., Tweed, T. S., & Cruickshanks, K. J. (2015). Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties Among Adults With Normal Audiograms: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Ear and Hearing, 36(6), e290–e299.

5 — Impact on Functional Communication Ability

5 — Impact on Functional Communication Ability

Although it is difficult to objectively diagnose this condition, data clearly show that it has a serious effect on functional communication ability. In addition to difficulty hearing in background noise, there is an extensive list of emotions and behaviors associated with hidden hearing loss.

- Source: Mealings, K., Yeend, I., Valderrama, J. T., Gilliver, M., Pang, J., Heeris, J., & Jackson, P. (2020). Discovering the Unmet Needs of People With Difficulties Understanding Speech in Noise and a Normal or Near-Normal Audiogram. American journal of audiology, 29(3), 329–355.

6 — Functional Communication Assessment

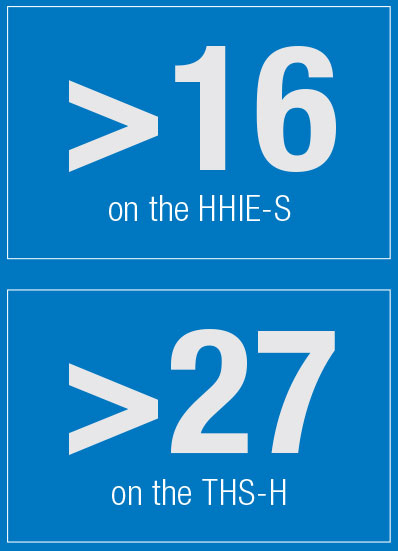

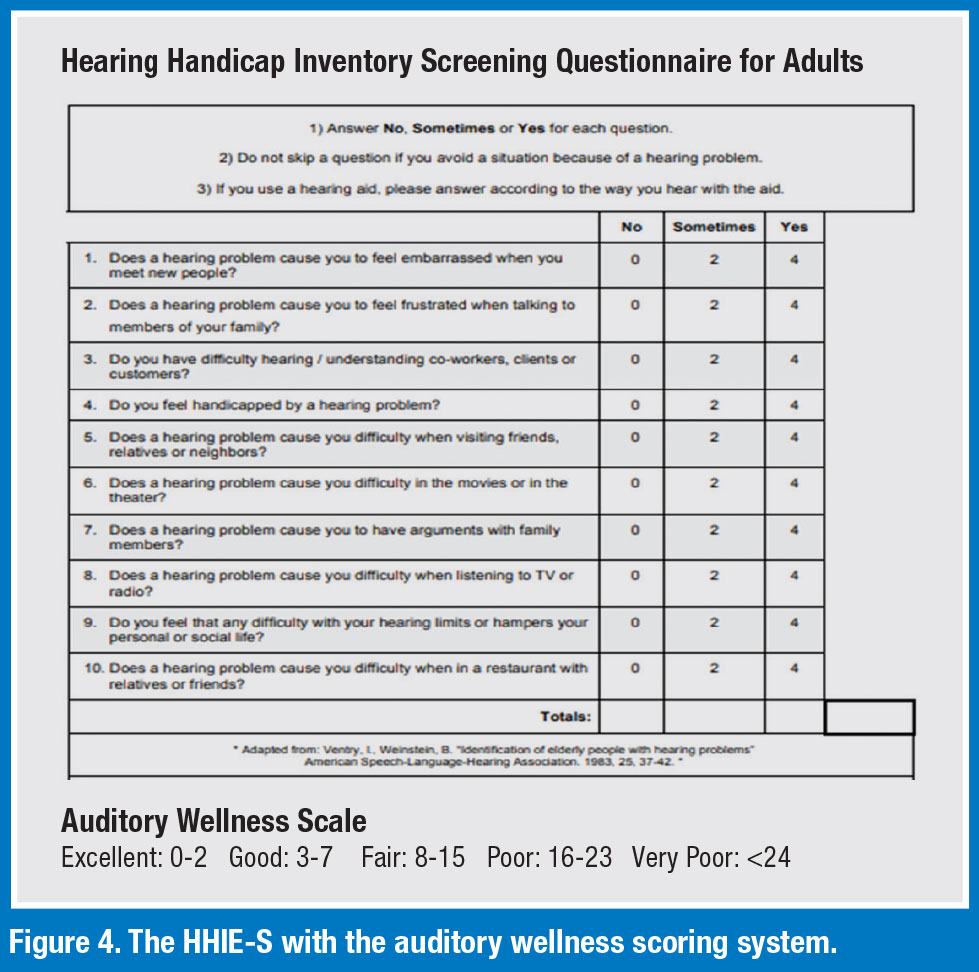

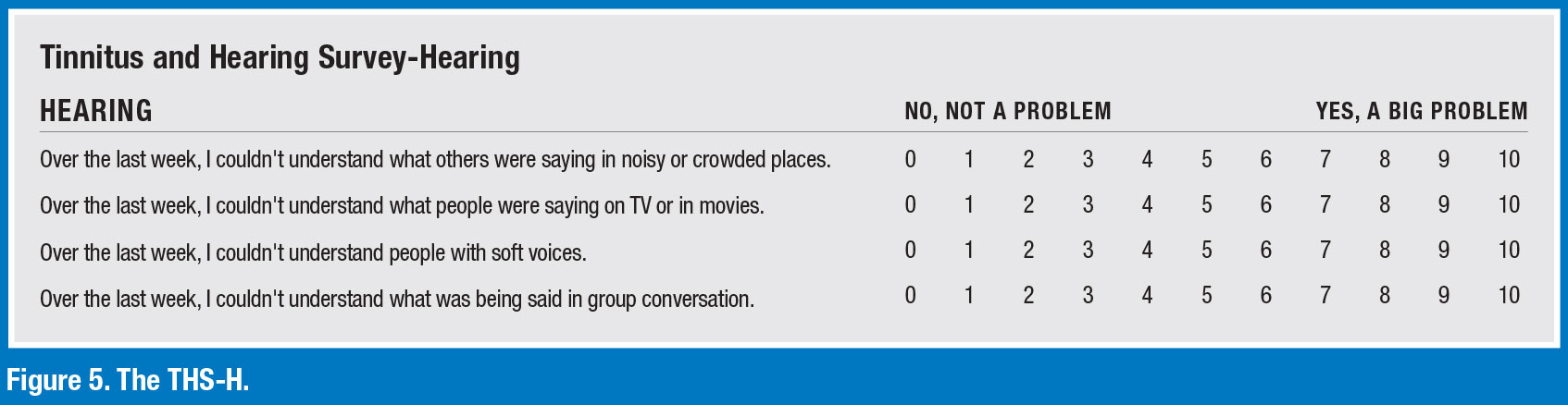

Given the relatively high prevalence of self-reported hearing difficulties among younger and middle-aged adults with normal audiograms, it recommended that a validated self-report or questionnaire be a part of the routine assessment process. Two self-reports that have been scientifically validated with this population are the family of Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults/Elderly (HHIA/E) questionnaires and the hearing component of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS-H).

Given the relatively high prevalence of self-reported hearing difficulties among younger and middle-aged adults with normal audiograms, it recommended that a validated self-report or questionnaire be a part of the routine assessment process. Two self-reports that have been scientifically validated with this population are the family of Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults/Elderly (HHIA/E) questionnaires and the hearing component of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS-H).

Figure 4 is the HHIE-S. It is comprised on 10 questions that can be administered during the routine hearing assessment. Note, there are three possible answers for each question that correspond to zero, one or two points. Simply add up the total number of points for the 10 questions to obtain a measure of the patient’s auditory wellness. According to Humes (2022) a score of 16 or higher on the HHIA/E-S is an indication of poor or very poor auditory wellness.

Figure 4 is the HHIE-S. It is comprised on 10 questions that can be administered during the routine hearing assessment. Note, there are three possible answers for each question that correspond to zero, one or two points. Simply add up the total number of points for the 10 questions to obtain a measure of the patient’s auditory wellness. According to Humes (2022) a score of 16 or higher on the HHIA/E-S is an indication of poor or very poor auditory wellness.

Another self-report that can be used clinically is a modified version of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS-H). Comprised of four questions, the THS-H can be completed by most patients in about 45 seconds. According to Davidson, et al (2024), a score of 27 or higher corresponds to significant hearing difficulty in everyday listening situations.

A score of 16 or higher on the HHIE-S and 27 or higher on the THS-H are indications that the individual would benefit from hearing aids.

- Sources: de Gruy, J. A., Spankovich, C., Hopper, S., Kelly, W., Witcher, R., & Vu, T. H. (2023). Defining Hearing Loss Severity Based on Pure Tone Audiometry and Self-Reported Perceived Hearing Difficulty, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 10.1055/a-2095-7002.

- Humes, L.E. (2022). 20Q: Assessing auditory wellness in older adults. AudiologyOnline, Article 28087. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

- Davidson, A., Ellis, G., Sherlock, L. P., Schurman, J., & Brungart, D. (2023). Rapid Assessment of Subjective Hearing Complaints With a Modified Version of the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey. Trends in hearing, 27, 23312165231198374.

7 — Hearing Aid Interventions

There are several studies that have examined the effectiveness of hearing aid interventions for young and middle-aged adults with self-reported hearing difficulties and normal audiograms. Highlights of each study are summarized next.

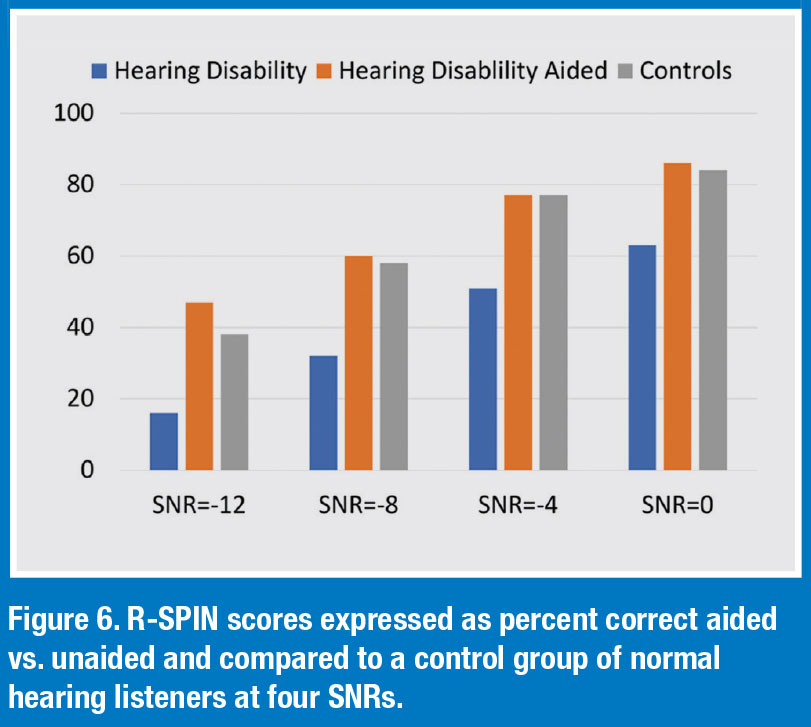

Study 1 Roup et al (2018)

Study 1 Roup et al (2018)

- All 20 participants had self-reported hearing problems per the HHIA but hearing sensitivity <25 dB for 250-8000 Hz. A control group of 20 young adults (19–27 years of age) without any self-reported hearing difficulties were included.

- As part of the pre-fitting testing, a battery of tests believed to be sensitive to auditory processing disorders were administered. Most of the participants in the experimental group performed abnormally on at least one of these tests.

- The experimental group was fitted bilaterally with hearing aids providing ~10 dB insertion gain. Laboratory testing included the Revised Speech in Noise (R-SPIN) test.

- Results of the aided R-SPIN aided shows significant benefit over unaided condition and comparable to control group. See Figure 6 for details.

- Although significant benefit was demonstrated for the experimental group, just 3 of the 17 participants opted to purchase the hearing aids at the end of the trial.

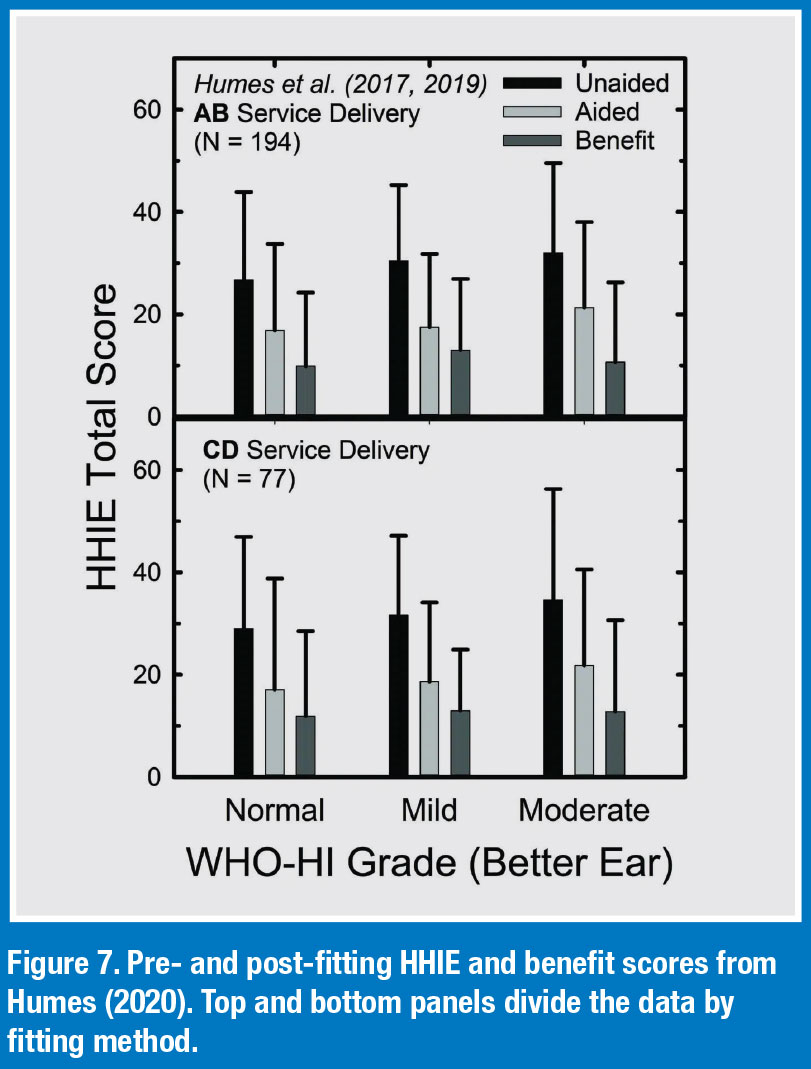

Study 2 Humes (2020)

Study 2 Humes (2020)

- 40 adults with normal audiograms were fitted with hearing aids and placed into one of two groups: A.) fitted under the watchful eye of an audiologist who followed best practices principles to fit the hearing aids (AB group) and B.) participates self-fitted the devices in the clinic with no direct involvement from an audiologist (CD group).

- The HHIE was administered before and a few weeks after the fitting of the devices.

- Results are illustrated in Figure 7. One, the unaided HHIE scores (black bars) for all three groups indicated that the unaided perceived hearing difficulties is about the same, with mean HHIE-Total scores ranging from about 27 to 33. Two, the light-grey bars in Figure 7 show the aided HHIE-Total scores and the mediumgrey bars show the HHIE benefit (unaided minus aided) scores. There were no significant differences (p>0.05) in mean HHIE benefit among the three groups in either panel of Figure 7. Interestingly, participants with normal hearing are reporting, on average, the same amount of benefit on the HHIA as those with moderate hearing loss.

- The self-fitted CD group experienced aided benefit that was similar to those fitted by audiologists using best practices. (AB group).

- At study completion, nearly 80% of those in the “normal” group purchased their hearing aids at the end of the trial, albeit at a significantly reduced rate relative to the commercial market.

Study 3 Mealings et al (2023)

Study 3 Mealings et al (2023)

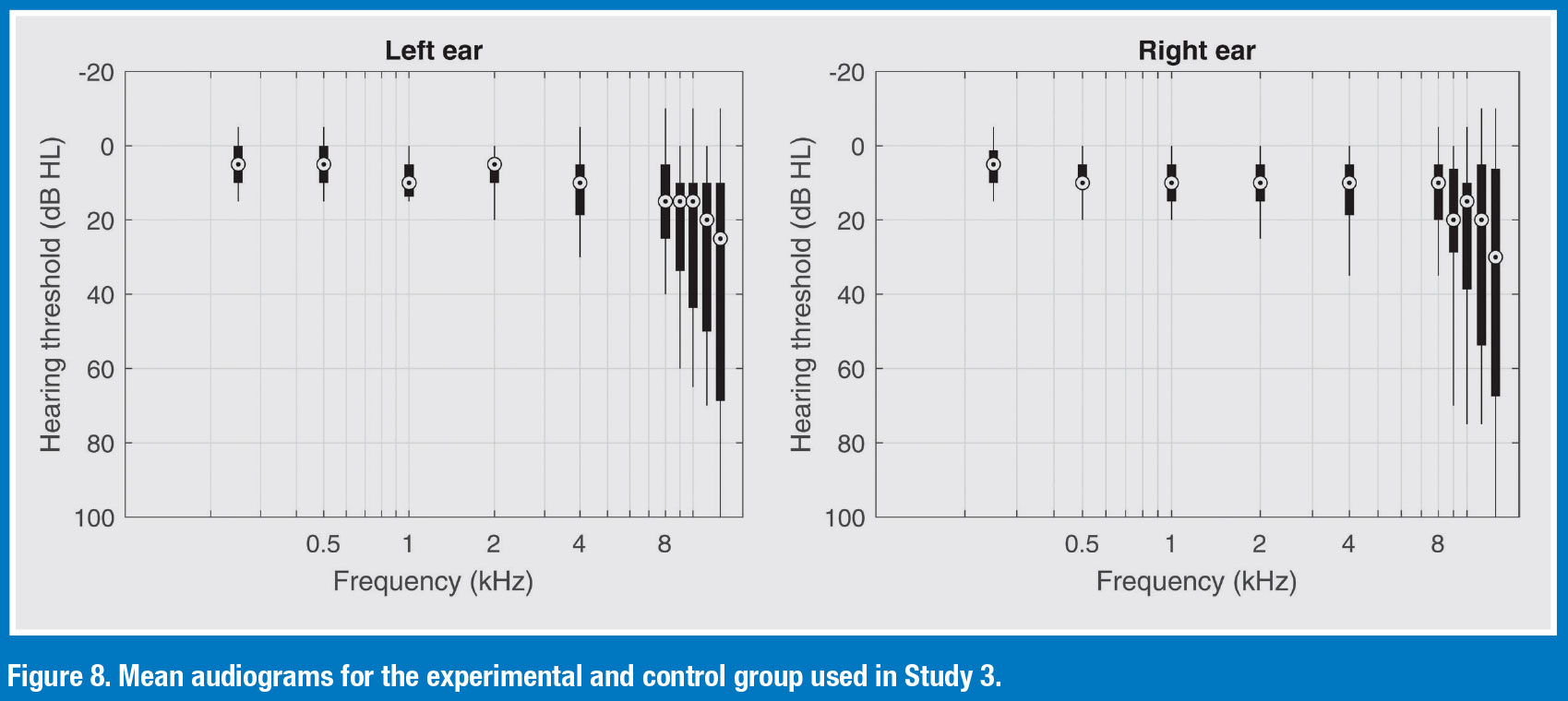

- Participants were 27 adults (17 females, 19–68 years old. Mean age was 36). All had an average hearing loss of <25 dB HL. The mean audiogram with range of individual thresholds are shown in Figure 8.

- This was a double-blinded case-control study where participants completed retrospective questionnaires (e.g., SADL, SSQ), real-world ecological momentary assessments (EMAs), speech-in-noise testing, and mental effort testing with and without hearing aids.

- The “experimental group” trialed mild-gain hearing aids with advanced directional processing. The “control group” also were fitted with hearing aids, but their hearing aids were programmed to 0 dB insertion gain, with no directionality.

- Results indicated that experimental participants reported significantly lower levels of hearing-in-noise difficulties when they were fitted with mild-gain hearing aids compared to no device. The placebo control group showed no difference between the aided and unaided conditions. The experimental participants reported significantly higher satisfaction with the devices than those in the placebo control group.

- For the real-world EMA, the experimental group reported a significantly better hearing experience when they were aided compared with unaided. The placebo group did not.

- Despite the real-world benefit reported by the participants (91% reported improved speech understanding in background noise), when given the option of buying the hearing aids for a purchase price of ~$3500, none of them agreed to this option.

Study 4 Davidson et al (2024)

- 186 US Miliary Service Members who wore hearing aids were surveyed using the THS-H.

- The average age of the participants was about 35 years old

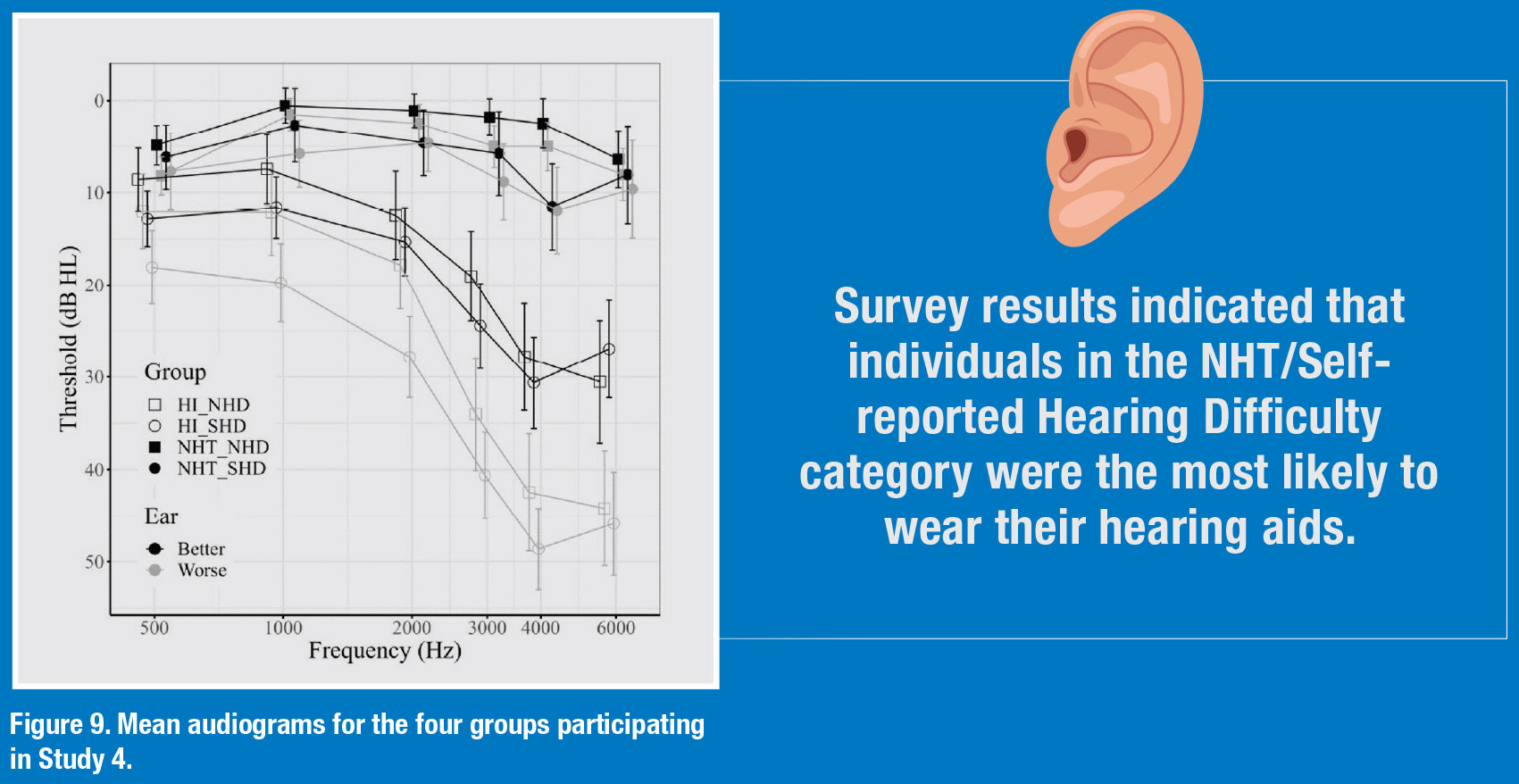

- The participants were divided into four groups (See Figure 9):

- Hearing loss (HL) and no self-reported hearing difficulty

- Hearing loss (HL) and self-reported hearing difficulty

- Normal hearing threshold (NHT) and no self-reported hearing difficulty

- Normal hearing threshold (NHT) and self-reported hearing difficulty

- Survey results indicated that individuals in the NHT/Selfreported Hearing Difficulty category were the most likely to wear their hearing aids.

- ~95% of those self-reporting hearing difficulties said they worn their hearing aids every day.

- Those that have no self-reported hearing difficulty, regardless of hearing loss, were highly likely to discontinue hearing aid use within a month or two.

- Individuals in the Self-reported Hearing Difficulty categories were 20x more likely than individuals in the No Self-reported Hearing Difficulty categories to report benefit.

- Sources: Roup, C. M., Post, E., & Lewis, J. (2018). Mild-Gain Hearing Aids as a Treatment for Adults with Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(6), 477–494.

- Humes LE. (2020). What is “normal hearing” for older adults and can “normal-hearing older adults” benefit from hearing care intervention? Hearing Review.27(7).12-18

- Mealings, K., Valderrama, J. T., Mejia, J., Yeend, I., Beach, E. F., & Edwards, B. (2024). Hearing Aids Reduce Self-Perceived Difficulties in Noise for Listeners With Normal Audiograms. Ear and Hearing, 45(1), 151–163.

- Davidson, A. J., Ellis, G. M., Jenkins, K., Kokx-Ryan, M., & Brungart, D. S. (2024). Examining the Use and Benefits of Low-/Mild-Gain Hearing Aids in Service Members with Normal Hearing Thresholds and Self-Reported Hearing Difficulties. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 12(5), 578.

8 — Clinical Implications

8 — Clinical Implications

- Results from these four studies clearly support the use of hearing aids as a suitable intervention strategy for those who self-report hearing difficulties and have normal hearing on the traditional pure tone audiogram.

- Individuals with normal audiograms and self-reported hearing difficulties experience benefit from hearing aids that is comparable to those with mild and moderate hearing loss.

- Even though benefit is easily established in this group, cost is a significant factor in the acquisition of hearing aids.

- Study 2 suggests that OTC and other direct-to-consumer devices could be a suitable low-cost alternative that yields outcomes similar to those derived from the traditional in-person dispensing model.

- Adults with normal hearing and self-reported hearing loss are still largely an untapped market segment that could benefit from hearing device interventions. This group has unique needs relative to prescription hearing aid wearers. They might benefit from hearing device innovations that have the appearance of consumer earbuds that can be worn all day (15-plus hours/day) without the battery being recharged and excellent sound quality in noise at a price point of under $500 per pair.

- Given the apparent low margins associated with successfully fitting hearing aids on this group, audiologists should consider the provision of direct-to- consumer device options. ■